Texts in Context:

The Roman Revolution

By Gabriel Blanchard

Rome had forever forsworn kings; she had reconciled the Orders; she had defeated her ghoulish rival Carthage. What remained, for Republic to become Empire?

Tempus Classicus

In the last month, we’ve rapidly reviewed a good six hundred years of Roman history; yet, in all that time, we’ve only caught up with our Author Bank as far as one Roman writer, the playwright Terence. Most of our Romans come either from the period we’re looking at today, or else from later periods to which the Empire was a fact of life, not a slowly-closing vise some people vainly tried to hold open.

After razing Carthage, Rome had time to ferment in her own internal conflicts again—and ferment she did, right up until the Battle of Actium in 31 BC, which left Julius Cæsar Octavianus (the adoptive son of the lately-deceased Julius Cæsar) the undisputed master of Roman politics.1 For the intervening hundred and fifteen years, intrigue erupting into violence was the order of the day. It may not be up to the refined standard set by the Athenian tragedians; but there is an irony all the same in the fact that Rome, later revered as the supreme symbol of harmony and law, began her “classical” period with an unorganized, slow-motion civil war.

The Sun Sets on the Republic

We need not go through every conflict, shock, and reversal of this long century—the tragedy of the Gracchi; the rivalry of Marius and Sulla; Roman expansion into Macedonia and Mauretania, Lusitania and Lydia, Cyrenaica and Cilicia. Suffice it to say that little things like assuming dictatorships, purging political rivals, killing tribunes, and marching against Rome with one’s legions, became—not normal, never that, but—conceivable.

By 49 BC, when Julius Cæsar and Pompey the Great had long since changed from allies to enemies, and Cæsar decided to lead his troops toward the city, it was an extreme move, but not an incomprehensible one—as it had been thirty years earlier when Cæsar’s uncle, Gaius Marius, normally a brilliant and fearless tactician, had been reduced to dithering by the news that his enemy Cornelius Sulla had crossed Rome’s hallowed border with his legions. Strange to say, it was during this mælstrom of war between Cæsar and Senate that Cicero is widely believed to have written many of his finest works of philosophy: Dē Finibus Bonōrum et Malōrum (“The Ends of Good and Evil”), Lælius dē Amīcitiā (“Læly, on Friendship”), Dē Officiīs (“Duties”), Dē Natūrā Deōrum (“The Nature of the Gods”), and possibly Dē Lēgibus (“The Laws”).

The civil war was not especially long—only about four years—but it ended with Pompey, who had made himself the champion of an independent Senate, dead, and Cæsar declared dictator in perpetuo. This was a specific, unprecedented reversal of the usual Roman habit of imposing term limits. Little wonder, maybe, that some persons felt it necessary to limit his term by other means than law.

Then again, Cassius may have done his own cause more harm than good. Cæsar had not only mourned Pompey, which anyone might have done for show: he had declared a general amnesty, allowing many of his bitterest political rivals to return home as if nothing had happened. He had adopted a son, certainly—his great-nephew Octavius, who took his adoptive father’s name with a distinguishing cognōmen2 based on his old name, making him Gaius Julius Cæsar Octavianus—so there was a possible heir to Cæsar’s powers; but only if he tried passing them on to an heir. Perhaps, if he had died a natural death, his office would have died with him. But Cassius Longinus, Junius Brutus, and the rest did not trust Cæsar to await that outcome. And one cannot help but feel it a pardonable distrust.

The Ides of March, And What Happened After Them

The assassination of Julius Cæsar, in 44 BC—what am I even saying? You know this already. Calpurnia, omens, “Cæsar shall forth,” et tu Brute, and so on.

Salus populi suprema lex esto.

The well-being of the People shall be the highest law.P. Tullius Cicero, Laws, Book III

We may get the impression from Shakespeare’s play that public sentiment turned back toward Cæsar’s cause unanimously and on a dime, or at least on a “Friends, Romans, countrymen,” but this understandably compresses the time scale. The assassins (or līberātōrēs, “deliverers,” as they styled themselves) remained practically immune to consequences for a surprisingly long time, despite not only Antony’s presence but even the return of Cæsar’s heir, Octavian. This was thanks in no small part to Cicero, who approved of the assassination and directed the full force of his eloquence to persuading the Senate, and keeping it persuaded, to side with the līberātōrēs. A full month later, after the funeral, popular feeling against them was barely strong enough to fuel shoddy attempts at reprisals; when the assassins left Italy, in August, even then, it was (on paper) to go and govern territories in the east, though Brutus at least had been privately considering exile. The new civil war was brewing, but it did not actually break out until January of 43—nearly a year after the murder.

It was a strange affair when it did break. Brutus and Cassius, ostensibly sent there to govern, ravaged the eastern provinces for men to serve in their armies, and for the food and money they needed to keep them. Cicero was in Rome, playing the dangerous game of trying to keep Octavian and the Senate together, against Antony, and in favor of or at worst neutral to the assassins; but even his silver tongue could not maintain this unnatural pattern forever.

Nightfall on the Republic

By the autumn, the Second Triumvirate3 had been formed. Octavian, Antony, and Brutus’ brother-in-law Lepidus: the heir and allies of Cæsar were reunited, and the to-be-expected proscriptions of troublesome citizens followed. Octavian argued against it for days, but ultimately, Cicero was put on the list. Like Cæsar, he was widely respected and even beloved by the populace, and many people simply would not report that they had seen him; Cicero’s own slaves would not give him up, but, when he was attempting to flee for Greece, a freedman of his brother’s tipped off the authorities. He is reported to have met his death with immense calm, telling the centurion, “Just make it clean if you can.”

In 42, the Cæsarian party mopped up the assassins at Philippi. Cassius and Brutus, after the disastrous battle, both committed suicide. Thereafter, Octavian saw to affairs in the west, while Antony attended to the eastern provinces.

Nonetheless, the ensuing decade still saw little peace: the longer Antony stayed in the east, the more enmeshed he became with Cleopatra VII, the last independent Queen of Egypt; meanwhile, for his part, Octavian delayed and delayed and, in the end, just didn’t send promised funds and men east. Antony fought a variety of wars in Syria, Mesopotamia, and the Caucasus Mountains, funded largely by Cleopatra and with mixed success. Then, in 34 BC, Antony formally broke with Octavian: he declared Cleopatra’s son Cæsarion the true heir of Julius Cæsar, and assigned realms all over northern Africa and the Near East, including Roman territories, to the twins he had had with Cleopatra.4 Predictably, this meant war—the last civil war of the Republic.

It was waged from 32 to 30, and was decided right in the middle, at the Battle of Actium in 31 BC. The Egyptian side lost; it was converted into a Roman province, under the rule of Octavian, who legally became the new pharaoh. When he returned to Rome, he no longer had any serious rival for power. The rule of the entire Mediterranean world had devolved upon a single man: the commander-in-chief, in Latin the imperātor, of the city of Rome. But let us move east again …

1Less because Octavian’s victory over Cleopatra and Antony was impressive, though admittedly it was a rout; still, his cause was helped much more by all his rivals being dead (very public-spirited on their part). Some historians instead place the Republican-Imperial cutoff date in 27 BC; this is when Octavian was awarded an unprecedented title by the Senate: “Exalted One,” or in Latin Augustus.

2A cognōmen was an optional third part of a Roman name (which normally consisted in a prænōmen, or personal name, and a nōmen, or family name). Cognōmina were often used to distinguish one branch of a large family from another: e.g., the Cæsarēs were a branch of the ancient Juliī. However, not everyone had a cognōmen. They were usually “awarded,” officially or unofficially, in recognition of some noteworthy trait or accomplishment—like Āfricānus for the defeat of Hannibal at Zama, or Cicerō, which literally means “chickpea” but probably referred to a prominent wart.

3Unlike the First Triumvirate, an informal, private agreement among Cæsar, Pompey, and Crassus (whose wallet was of great use to the triumvirs), the Second Triumvirate was public and legally binding.

4Cæsarion was the illegitimate son of Julius Cæsar. Antony’s twins with her were named Alexander Helios and Cleopatra Selene.

Gabriel Blanchard is CLT’s editor at large. He lives in Baltimore, MD.

Thank you for reading the Journal.

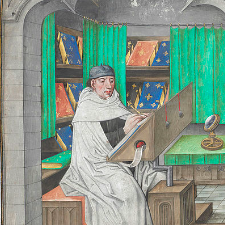

Published on 9th September, 2024. Page image of The Death of Cæsar (1850) by Jean-Léon Gérôme.