Texts in Context:

An Outline of Islam

By Gabriel Blanchard

Having introduced Islam to the world, and bearing in mind the important role it will play in later history, let us take a closer look at what it actually consists in.

The Five Pillars

Last week, we brought Islamic history from its beginnings in the early seventh century down to the founding of the Umayyad Caliphate. But what is Islam in the first place? And considering the circumstances, why was it almost another five centuries before the Crusades began?

The traditional list of the Five Pillars of Islam seems like a good place to start. Certainly, all branches of Islam accept these five practices as core. They are:

1. شَهَادَة [shahādah], or profession of the Muslim faith (normally in the formula “There is no god but God; Muhammad is the prophet of God”)

2. صلاة [ṣalah], or prayer (normally five times daily, facing Mecca)

3. زكاة [zakāt], or almsgiving (normally one-fortieth of one’s income)

4. صوم [ṣawm], fasting (especially from dawn to dusk in the month of Ramadan,1 when Muhammad’s revelations began)

5. حَجّ [hajj], pilgrimage to the Cube2 (for those who can afford to do so)

These are summaries, of course, with much unstated context. (Many people are excused from the third and fourth duties, for instance, on grounds of poverty, health conditions, pregnancy, etc.) Shahadah implies most Muslim theology, for example, by hinting at the doctrine of God’s tawḥīd, or absolute unity and transcendence, but the rest is left unsaid. Very little is said directly even about the Quran. And nothing is said of what we might—very loosely—call the denominations of Islam.

Wheels Within Wheels

Most of us have heard the names of a few Muslim sects or parties before, probably without explanations or context. The single largest variety of Islam, around 85% of the faith’s adherents, is Sunni Islam (which means something like “traditionalists” or “orthodox”). They view the Rashidun Caliphate as having been just what it was called: “rightly guided” and holding just authority. On that point, they differ with the Shia, a term that can be rendered in English as “partisans” or “loyalists.” Shia believe that the prophet’s own descendants through his son-in-law Ali are a dynasty with divine right, whose head is the إِمَام [imām], meaning “leader” or “paragon.” Sunnis also speak of imams, but merely as teachers; Shia consider the Imam as the infallible interpreter of the Quran (though most believe that he is now in a state of supernatural concealment). These two groups, Sunni and Shia, are the closest analogue to “denominations” in the Christian sense.3 Equivalent groups in Islam, such as Ahmadis and Ibadis, make up less than 2% of the religion’s adherents.4

Another variety of Islam tends to cut across these divisions, certainly across the Sunni-Shia divide: the Sufis. This is the mystical side of Islam, which seeks not only to honor God with worship and righteous living, but to be in some sense lovingly united with him. Sufism consists in several societies, typically called “orders” in the West on analogy with monastic orders (though membership in Sufi orders is not exclusive, and celibacy is not a standard element); the best-known Sufi Order is likely the Mevlevis, colloquially called the “Whirling Dervishes,” founded by the celebrated Persian poet Rumi.

Reason is the shadow cast by God; God is the sun.

Jalal ad-Din Muhammad Balkhi (a.k.a. Rumi), The Spiritual Couplets

There is another kind of variety in Islam—but at this point, the reader may become downright dismayed; how many kinds-of-kinds can there be! Unluckily, the answer is “all of them.” But this is our last set of subdivisions, and we will only scratch the surface with regard to Islam’s many madhahib (màð-à-hēb, or madhhab [màð-hàb] in the singular). These are schools of fiqh (fĭk), which is something between theology and jurisprudence. Each madhhab has its own view of how literally the Quran should be interpreted, what traditions about the Prophet are correct, how much human reason can be trusted, and what role precedent and analogy should play in decisions about new issues. In states where Islam is the national religion, many modern governments are eclectic, taking some rulings from this madhhab and some from that. But, since the issue of Islam as a state religion has come up, we should address two additional elephants in the room.

Jihad and Sharia

You may have heard that Islam (or some specific branch of Islam) has jihad, or war against infidels, as a sixth pillar of the faith; or that Muslims want to impose sharia law, which means Islamic totalitarianism. The only thing to be said about these claims is that they are not true. For one thing, the word sharia just means “law,” in general. (An individual Muslim or Islamic group might desire a totalitarian law-code, but that no more defines Islam than Christians who support monarchy define Christianity.)

The error might arise from a garbled understanding of the Twelver Shiites, the largest group of Shia. Their explanation of Islam begins not with the five pillars, but with five doctrines; it proceeds from there to ten practical “ramifications” (the five pillars and five further practices), one of which is called jihad. The thing is, jihad doesn’t just mean “war”: It can refer to anything that takes strenuous effort. The ascetic life of an ancient ḥanīf pursuing self-mastery was a jihad; the same word could be used for the long effort of William Wilberforce to end the slave trade. In the precepts of Twelver Shia, the jihad in question is that of devoting oneself to righteousness in the face of temptation.

It is true that most schools of Islam permit Muslims to wage war on non-Muslims on some grounds; and yes, the caliphs did regard war as a legitimate means of extending their power. But there is no command to exterminate non-Muslims in any branch of Islam. It is also true that historical Muslim practice involved imposing dhimmi status, a kind of second-class citizenship, upon other “Peoples of the Book”—i.e., faiths which possess a revelation Muslims acknowledge as sacred though incomplete.5 But it is worth saying that dhimmi status protected its recipients at the same time that it limited their rights and privileges. If we want to play the Who Was Meaner game,6 and we happen to be Christians and/or of European ancestry, we must contend with the fact that Christian Europe equally imposed a protected-but-second-class status on Jews living in Christendom, and did so without usually extending the same generosity to Muslims.

But the Who Was Meaner game is not the only way we can think about Islam, or its only common ground with Christianity. Muslims claim descent from Abraham, and recognize the other Abrahamic faiths7 as “People of the Book,” but also hold that the second-greatest of all God’s prophets was ‘Īsā ibn Maryam: that is, Jesus, the son of Mary. As a matter of fact, Islam was viewed by Christian theologians for centuries not as a separate religion, but a new Christian heresy.

This is a part (albeit probably a small part) of why the Crusades as we know them begin at the end of the eleventh century, rather than in the middle of the eighth, say. Ideally, Christians weren’t supposed to wage war at all—taking up arms even for a just, defensive cause was typically followed by long penances in early medieval Christianity—but they especially were not meant to wage war against fellow Christians, however grave their dispute might be.

1The Muslim religious calendar is a strictly lunar one, with twelve months of either twenty-nine or thirty days. It therefore falls behind the Gregorian and other solar calendars at a rate of eleven days per year, and all its months move a little less than two weeks earlier each year.

2The Kaaba (“cube” in Arabic) is known by Muslims to predate Muhammad—indeed, they believe it was originally built by Abraham. After he conquered Mecca, Muhammad cleansed the Cube of the idols it had hitherto contained; this is regarded by Muslims as a restoration to its original purpose.

3Though “groups of denominations” might be a better way to think of it, a bit like Christian terms such as Pentecostal or Methodist: These terms point to some shared history and beliefs, but not necessarily to a single ecclesiastical body—United Methodists, members of the A. M. E. Church, and Free Methodists are all “Methodists,” but their governing bodies are independent.

4Shia form the majority in Azerbaijan, Iran, and Iraq, and are an important minority in Bahrain, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Turkey, and Yemen. Ibadis, a denomination descended from the Kharijites, are a majority in Oman. Elsewhere, Muslims are usually Sunni.

5The Muslim view of Judaic and Christian Scriptures is that they were legitimate originally, but have become corrupted. Three prophets in particular, Mūsā (Moses), Dawud (David), and ‘Īsā (Jesus), received a book and transmitted it faithfully to their followers; these books were the Tawrat (Torah), Zabur (Psalms), and Injīl (Gospel). The Quran is the supreme revelation of the four, sent partly to correct the errors of Jews and Christians.

6This cheap substitute for fun (made of 100% toxic materials) is designed for children ages eight to eighty. The loudest player goes first, while the most correct player is unknowable. The game is over at the Second Coming or the heat death of the universe, whichever is sooner.

7The expression “the Abrahamic religions” applies primarily to Christianity, Islam, and Judaism. There are a handful of others, such as the Druze faith and Bahá’í faiths. All originated in the Middle East; most are descended from Judaism (either directly or through some intermediate offshoot), and revere Abraham as a foundational figure.

Gabriel Blanchard is CLT’s editor at large. He lives in Baltimore, MD.

If you enjoyed this piece, be sure to take a listen to our podcast, Anchored.

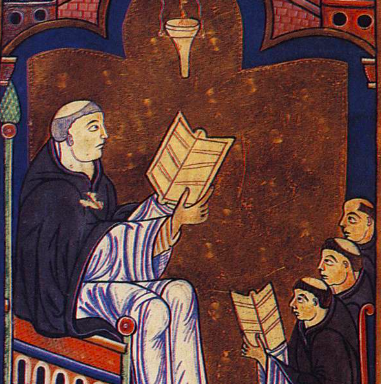

Published on 9th December, 2024. Page image of a fourteenth-century tiled mihrab (a wall niche used in mosques and other buildings to indicate the direction of Mecca), originally from Isfahan, Iran.