Texts in Context:

1066 and All That

By Gabriel Blanchard

England as we know it, the England of the High Middle Ages and thereafter, finally attains recognizable shape.

The numbered shires are: 1. Middlesex; 2. Rutland; 3. Huntingdonshire; and 4. Bedfordshire.

The abbreviations are: "Bucks.", Buckinghamshire; "Cambs.", Cambridgeshire;

"Northants.", Northamptonshire; "Oxon.", Oxfordshire; and "Worcs.", Worcestershire.

Ænglalond

We now return to “the Land of the Angles,” which is in for some changes. Sadly, we must pass over most of the story the House of Wessex, the first dynasty to rule England as such (beginning in 927 under Alfred the Great‘s grandson, Athelstan). We have to do only with the last king of that house, St. Edward the Confessor.1 He came to the throne in the summer of 1042, and died in 1066 on the twelfth day of Christmas (5 January). His reign was mostly peaceful militarily, and he is honored as the re-founder of Westminster Abbey, but he had no children. This set off a succession crisis.

The House of Wessex had ties to many other noble and royal houses, which could furnish an heir or make everything worse. There were the House of Godwin, the late saint’s in-laws; he had intensely disliked them—possibly for telling the same terrible jokes at every family gathering, and almost certainly for having blinded and killed his younger brother—but he at least considered naming Harold Godwinson,2 his brother-in-law, as the heir. Wessex also had ties to the Danish royal House of Knýtlinga; in fact, St. Edward’s predecessor had been his half-brother Harthacnut, son of Cnut the Great (for whom the Knýtlingar are named). That house in turn had dynasts outside Denmark. The current Duke of Normandy had a claim on the throne through Knýtlinga ancestry, and St. Edward had considered naming him his heir as well. Unluckily, even if he made his mind up, he did not make his mind clear.

In any event, both men claimed to be the rightful king, and since Godwinson had the benefit of already being in England, he was able to be crowned King Harold II the very next day. He would be the last Anglo-Saxon king of the realm.

Plans abroad to contest the succession were rapidly clear; it was a matter of months before the king was due to meet this aspiring conqueror in battle—a perilous warrior descended from Vikings, whose victory would alter the monarchy, the history, and the very language of the English. But of course King Harold II won the Battle of Stamford Bridge, and King Harald Hardrada of Norway (who had been attempting to revive the North Sea Empire) was killed. Norway would never again be a thorn in the side of England.

Unluckily, Duke William of Normandy was queued up next, with a program that essentially said “All that Harald Hardrada stuff, but with me in charge, obviously.” Stamford Bridge had been fought in Yorkshire, so King Harold was there (as were his army, who had been a great help to him in fighting the battle). William, however, rudely landed in Sussex, over two hundred miles to the south. King Harold II and his army had to march the whole distance in the space of about three weeks—a pace of more than ten miles per day.3 Neither the king nor his men were in any mood to have a Battle of Hastings at the end of the trek. Nonetheless, William, who does strike one as rather the selfish type, insisted. Harold was killed in it, and that was the end of that.

Bretagne4

Historians used to wax indignant about the “Norman yoke” to which England was hereafter subject, but the Norman Conquest probably impacted most ordinary people very little. The average peasant used to pay taxes to a half-Scandinavian thane with a vaguely Rhineland accent; now he paid them to a half-Scandinavian baron with a vaguely Parisian accent; et puis après?5

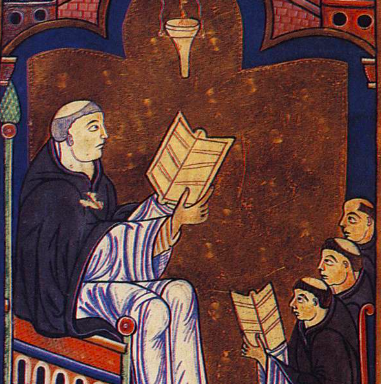

Still, there were some changes. Though slavery was not legally abolished yet, the actual number of slaves in the country dwindled from few to practically zero—the Domesday Book of 1086, a collection of census data, records approximately 28,000 slaves in a population rapidly approaching two million (and there had been more slaves against a smaller populace twenty years before). On the other hand, many Anglo-Saxons fled the country, either for elsewhere in the British Isles or for the Continent. Some did well abroad; King Malcolm III of Scotland (the Malcolm of “the Scottish play”) married St. Margaret of Wessex, a great-niece of the Confessor and a promoter of reform among the Scottish clergy. In the Kingdom of England itself, however, there was ethnic discrimination against Anglo-Saxons. Both the nobility and the offices of the Church were peopled almost exclusively by Normans for over a hundred years.

For heathen heart that puts her trust

In reeking tube and iron shard,

All valiant dust that builds on dust,

And guarding calls, not Thee to guard,

For frantic boast and foolish word—

Thy mercy on Thy people, Lord!Rudyard Kipling, Recessional

Yet the most profound effect of the Conquest may have been on the English language. Between 1066 and the mid-twelfth century, our mother tongue evolved from Late Anglo-Saxon into early Middle English. The grammatical system changed drastically, losing most of its inflections6 and instead becoming mainly analytic (based on word order). Already influenced by the Norse-speaking Danelaw, English now began absorbing an immense quantity of words from Norman French—and, since many scribes came from the Continent now, French spelling came with them. Documents in Middle English start to look, not familiar exactly, but recognizable. For instance, without study, no one today can read text like this (though it sounds less alien in spoken form):

Fæder ure, þu þe eart on heofonum, si þin nama gehalgod. Tobecume þin rice. Geƿurþe ðin ƿilla on eorðen sƿa sƿa on heofonum. Urne gedæȝƿamlican hlaf syle us todæg. And forgyf us ure gyltas sƿa sƿa ƿe forgyfað urum gyltendum. And ne gelæd þu us on costnunge, ac alys us of yfele. Soþlice.

But this, while difficult, probably does read like something that’s vaguely familiar:

Oure Fadir þat art in heuenes, haleƿid be þi name; þi kyngdom come to; be þi ƿille done, in erðe as in heuene. Ȝyue to vs þis dai oure breed oure oðir substaunce, and forȝyue to vs oure dettis, as ƿe forȝyuen to oure dettouris; and lede vs not in to temptacioun, but delyuere vs fro yuel. Amen.7

It used to be thought that the Anglo-Saxons wiped out the Romano-Brythonic populace, except in westerly enclaves and in the north; this was the explanation offered for why the local Brythonic language (and British Latin) had so little impact on English. That theory has become controversial, and there are a few ways Brythonic might have influenced English after all. For an example, take the English present progressive tense, i.e., the construction we actually use as a present tense, as in “I am reading” rather than “I read.” (The latter form normally indicates what’s called a gnomic verb, which conveys habitual activity or general truth, not current action.) The present progressive uses the verb “to be” and a participle, always ending in “-ing”; cross-linguistically, this is an extremely uncommon and oddly complex way of forming the present tense—but it does also appear in Celtic languages.

Germanic and possible Celtic roots aside, however, we have just seen the beginning of a huge inflow of Romance vocabulary. Anglo-Saxon did already have a tidy number of Latin loan-words, since Latin was the language of education and of the Church; “candle” (candēla), “chalice” (calix), “noon” (nōna), “purple” (purpureus), ” “temple” (templum), and “wine” (vīnum), as well as certain place-name elements like “–wich” (vīcus), all entered Old English before 1066, along with hundreds more.

French, however, dwarfed even this sizable contribution. Words about state affairs, war, and the law abound: artillery, attorney, bureaucracy, finance, guard, justice, platoon, protocol, siege, sovereign, surveillance, treasury, treaty. Art, architecture, and culture present us with still more: arch, author, belfry, blue, façade, genre, humor, lintel, niche, pavilion, portrait, scarlet, and vault. Consider food-related terms like beef, caramel, cherry, endive, nutmeg, orange, pastry, pork, and venison. There are also phrases and proverbs that have been borrowed into English by the dozen, such as bête noir, force majeure, je ne sais quoi, noblesse oblige, and répondez s’il vous plaît (usually abbreviated RSVP).

Albion

There was one other respect in which the voyage of William the Conqueror would prove deeply important in the long run. Since the Romans had withdrawn in the early fifth century, the British Isles had been operating more in the orbit of northern Europe than that of the Mediterranean. Under the House of Normandy, that trend was reversed. It would be a long time yet before England was more than a regional power with modest cultural importance to the rest of Europe; but a road had been planned and paved, even if the people who would walk on it were as yet unborn.

*Pronunciation of English Shire Names

Bedfordshire: bĕd-fõŕd-shŕ

Berkshire: bäŕk-shŕ

Buckinghamshire: bŭk-ĭŋ-àm-shŕ

Cambridgeshire: kām-brĭj-shŕ

Cheshire: shĕ-shŕ

Cornwall: kõŕn-wäł

Cumbria: kŭm-brē-à

Derbyshire: däŕ-bē-shŕ

Devon: dĕ-vøn

Dorset: dõŕ-sĕt

Durham: dŕ-àm

Essex: ĕs-ĕks

Gloucestershire: glŏs-tŕ-shŕ

Hampshire: hâmp-shŕ

Herefordshire: hēŕ-fõŕd-shŕ

Hertfordshire: häŕt-fõŕd-shŕ

Huntingdonshire: hŭn-tĭŋ-døn-shŕ

Kent: kĕnt

Lancaster: lâŋ-kà-stŕ

Leicestershire: lĕs-tŕ-shŕ

Lincolnshire: lĭŋ-køn-shŕ

Middlesex: mĭd-ł-sĕks

Norfolk: nõŕ-føk

Northamptonshire: nõŕth-âmp-tøn-shŕ

Northumberland: nõŕth-ŭm-bŕ-lànd

Nottinghamshire: nŏt-ĭŋ-àm-shŕ

Oxfordshire: ŏks-fõŕd-shŕ

Rutland: rŭt-lànd

Shropshire: shrŏp-shŕ

Somerset: søm-ŕ-sĕt

Staffordshire: stă-føŕd-shŕ

Suffolk: sŭ-føk

Surrey: sŕ-ē

Sussex: sŭ-sĕks

Warwickshire: wäŕ-ĭk-shŕ

Westmoreland: wĕst-møŕ-lànd

Wiltshire: wĭłt-shŕ

Worcestershire: wüs-tŕ-shŕ

Yorkshire: yõŕk-shŕ

See our pronunciation guide for details on the symbols here; note that, as an ending, “-shire” rhymes with fur, not with fire. Two further points: According to the Domesday Book of 1086, Lancaster did not yet exist, most of its territory being subsumed under Yorkshire; and the four northernmost shires were not clearly considered part of England (Cumbria especially was associated more closely with Scotland, as a part of the former Kingdom of Strathclyde8). Map created based on a design by Wikimedia contributor Dr Greg, made available under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license (source).

1The numbering of English and later British monarchs conventionally begins only after the Conqueror. Hence, although he was the third king of England to bear the name Edward, St. Edward is distinguished by his epithet “the Confessor” (then a title for saints who were not martyred).

2Surnames had not yet come into use in English. Godwinson was not a last name in the modern sense, but a patronymic: i.e., Harold was the son of a man named Godwin, and any sons of Harold’s would have had the patronymic Haroldson, not Godwinson. (Modern surnames ending with –son likely started as patronymics, but began at some point to be passed down across generations.)

3For reference, the distance of a usual day’s hike for a group of healthy adults is around eight miles.

4Bretagne normally refers to Brittany, a peninsula in northwestern France. However, the early versions of the Arthurian cycle, largely written in Old French, are called la matière de Bretagne, for which the conventional English equivalent is “the matter of Britain.” Hence, Bretagne and Brittany are sometimes used as poetic names for Britain.

5Loosely translated, this phrase means, “So what?”

6Inflection does actually still exist even in Modern English, albeit vastly reduced. All nouns inflect for two numbers, and also for two cases—the nominative and the old oblique case of nouns, still present in Middle English, have collapsed into a single nominative-oblique case, but the possessive is still always distinguished. Personal and relative pronouns retain separate nominative and oblique forms, and so have three cases. Verbs inflect primarily for two tenses, present and past, indicating other tenses and most other elements of the verb through auxiliary words and word order; weak verbs inflect for the past tense with the ending –ed, while strong verbs do so via apophony, as in “sing, sang, sung”).

7The letters ð (eth) and þ (thorn) represent the th‘s of “this” and “thin,” though the distinction was not always observed. Ȝ (yogh) represented three sounds: the ch of Scottish “loch”; a sound like the “blurred” g of Spanish; and the y of “yes.” The letters u and v were considered forms of the same letter (v was used at the beginnings of words, u elsewhere; which sound was called for was determined by context). W did not yet exist; some writers used the rune ƿ (wynn), borrowed from futhorc.

8Scotland took shape largely out of the union of four realms: Fortriu, the Pictish kingdom of the northeast; Lothian, a part of the Anglian kingdom of Bernicia (a forerunner of Northumbria); Ystrad Clud, or Strathclyde, in the southwest; and in the west, the Irish kingdom of Dal Riata.

Gabriel Blanchard studied Classics at the University of Maryland, College Park, and is a proud uncle to seven nephews. He lives in Baltimore, MD.

If you enjoyed this piece, be sure to check out the official CLT podcast, Anchored. Thank you for reading.

Published on 24th February, 2025.