Abelard

An Author Profile

By Gabriel Blanchard

The intellectual revival that took place in eleventh and twelfth century Paris lies at the heart of western thought.

❧ Full name: Pierre Abélard (French), Petrus Abailardus (Latin), or Peter Abelard [pē-tŕ ăb-ĕ-läŕd; see our pronunciation guide for details]

❧ Dates: 1079–21 Apr. 1142

❧ Area active: Kingdom of France (principally the Duchy of Brittany and Île-de-France)

❧ Original language of writing: Medieval Latin

❧ Exemplary or important works: Sic et Non (“Yes and No”); Logica Ingredientibus (“Logic for Intermediate Students”)

Born in Brittany in or around 1079, Abelard came of age in a Christendom that was rapidly changing. Despite the feud between Rome and Constantinople culminating in the Great Schism,* even these quarrels were generally seen as less urgent than the threat posed by the Islamic powers, who had conquered everything from Pakistan to Portugal. Even a slightly forced Christian unity meant diplomatic relations, which meant cultural ones, which meant scholars from the well-preserved tradition of the east sometimes coming to the fragmented, half-literate west. The First Crusade and the Reconquista both put Catholic Christendom into prolonged (even if, ah, unfriendly) contact with Muslims and their learning, especially the treasury of Aristotle. An intellectual revival was already beginning in monasteries and cathedral schools in the late eleventh century—especially in large cities like Bologna, Oxford, Cologne, Rome, and above all Paris. It was here that our young scholar came around the turn of the twelfth century.

Abelard rapidly gained attention both for his personal brilliance and his gifts as a teacher. The hot topic of the day was the debate over realism and nominalism: are universals real, or are they polite fictions that serve entirely for practical purposes? Conventional philosophic orthodoxy (realism) was championed by one William of Champeaux, whose students founded the School of St. Victor. The “darker and edgier” school of thought (nominalism) more or less began with Roscellinus of Compiègne, who went from unconventional ideas to outright heresy when he applied nominalism to his doctrine of the Trinity. Though Roscellinus was convicted of tritheism and forced to recant, nominalism continued to flourish for centuries. Abelard set forth a new position in the debate, conceptualism, often described as a via media between nominalism and realism (and somewhat like Aristotle’s position on the Forms); yet he also contrived to offend both Champeaux and Roscellinus in rapid succession—he was reputed to be arrogant—so that, within his first five years in Paris, he was obliged to found his own school to be able to teach. Even this was by no means all bad: he kept and indeed improved his reputation as a masterful logician, and by 1113 he had moved on to the study of theology, which allowed him to become the head of the prestigious cathedral school of Notre-Dame. As it was increasingly the custom for professional academics to be clergy as well (which will be important shortly), he also became a canon** at this time.

The bulk of Abelard’s surviving and influential writings are philosophic and theological in nature: the most renowned is Sic et Non (“Yes and No”). In this work, he superficially adopted the technique of the florilegium, or anthology of quotations from the Church Fathers on a selection of given topics; florilegia were quite popular in the Middle Ages. But Abelard, instead of presenting a neatly-arranged list of pious commonplaces, put seemingly contradictory, jarring, or confusing quotations together, and outlines how students should use the techniques of dialectic and rhetoric to understand the nuances of these maxims. Different senses of a single word, different audiences, different situations being addressed—all could create an appearance of discord where, really, there was little or none. Abelard’s foes touted this as proof of his disrespect for the Fathers, even though, if one takes a moment to reflect, it is if anything the opposite: it prompts the reader to think out how apparent contradictions or paradoxes may in fact be fully harmonious, and thus encourages thoughtful acceptance of these authorities. The people calling it disrespectful were, in modern parlance, reacting to nothing but the book’s “vibe.”

Yet it was neither on account of his philosophy nor of his vanity—not directly, at least—that Abelard’s life soured. The same year he returned to Paris, he met a young woman named Héloïse,† reputed to be the most educated woman in Paris—and really, she may have been, considering that she knew not only standard-issue Latin, not only cultivated Greek, but the real test of linguistic mettle among the three, Hebrew. She lived under the care of her uncle, Fulbert, another canon at Notre-Dame. The twelfth century saw the dawn of courtly love—the troubadours, the Grail romances, the forerunners of the Divine Comedy; perhaps it was simply in the air. Whatever the reason, Abelard fell in love. He secured a position as Héloïse’s tutor, and it was a boy, whom they named Astrolabe.‡

There are many apparent contradictions and obscurities in the innumerable writings of the Church Fathers. Our respect for their authority should not stand in the way of our effort to reach the truth. The obscurity ... can be explained on many grounds, and can be discussed without defaming the good faith and insight of the Fathers.

Peter Abelard, Sic et Non, Prologue

Exactly how everything shook out was a matter of dispute at the time, and has remained such for nine hundred years: Abelard later reproached himself with having seduced his pupil, yet Héloïse angrily denied this, asserting throughout her life that their relationship had been one of intellectual equals. Probably no one, perhaps not even the lovers themselves, really knew. What is not in dispute is the cascade of misfortune which followed.

Fulbert was enraged when he discovered their affair. Abelard sought to appease Fulbert by marrying Héloïse, who, of course, would not hear a word of it at first. Marriage would be sure to ruin Abelard’s academic career: professional scholars were expected to be priests, and at this juncture in Catholic history, the rule of clerical celibacy was finally starting to be not only defined as church law but enforced as church law. So the compromise of a valid but secret marriage was attempted. That is, the “marriage” bit happened just fine, and then Fulbert betrayed the pair’s trust by publicizing the marriage. Trying to protect her husband, Héloïse flatly denied the truth, making her uncle even angrier. Abelard spirited her into hiding with a convent of nuns (she took no vows at the time, but did wear their habit and follow their way of life). Fulbert, deprived of his beloved niece-slash-target, now turned to hired goons, whom he directed to break into his new nephew’s home and castrate him; on top of everything that goes with being involuntarily and unexpectedly castrated, this also made Abelard strictly ineligible for any further advancement in the Church, as canon law forbade it (probably in continuity with Deuteronomy 23:1).

To do the Parisian public justice, not only were the said goons punished by law, but aspiring godfather Fulbert’s reputation was ruined. Even so, the damage was done as far as Abelard’s life and prospects were concerned—besides which, more than one of the many enemies he had made did have nasty and quite public laughs at his expense. He retired to a monastery, and instructed his wife to become a nun in reality as well as appearance. She protested, but obeyed; mostly—but she too is on the Author Bank, and something must be left for her story!

Besides, Abelard’s tale of woes had only just begun. The Historia Calamitatum, which means in English just what the Latin sounds like, may strike the modern reader as self-pitying, and it is likely that, at minimum, Abelard’s perceptions were colored by his own faults; yet there is no denying that he was mistreated and hounded for years and even decades on end. He had a series of miserable living arrangements, mostly in undisciplined and unfriendly houses of religion; he toyed with the idea of leaving Christian lands as such behind, in order to find a place to hide in peace. Some of this again seems to have been partly his own fault, in that he liked needling his fellow monks over trivialities, but the resulting humiliations were out of all proportion to the offense of “being obnoxious.” Moreover, in the last decades of his life he was beset by repeated accusations of heresy, on the part of people who appear to have been mainly concerned not with whether Abelard was a heretic, but whether they had charges to bring against him: everything was marshaled to that purpose by his enemies, from professed errors in his definition of the Atonement, potentially a serious problem indeed, to the fact that he named a convent he founded after the Holy Ghost and not “the whole Trinity” (which sounds more in-keeping with the King of Hearts’ claim that Rule Forty-Two is the oldest in the book).

Doctrinally, this theme came to a head in a conflict with St. Bernard of Clairvaux, the great Cistercian reformer, albeit he does not show in his best light in this story. Having extracted certain propositions that he asserted were from Abelard, St. Bernard convinced a local council to condemn them before hearing any defense from Abelard; the latter appealed to the Pope, who promptly excommunicated him, imposed perpetual silence upon him, and piled yet further penalties on him besides. Yet here at last, some small easement was granted to the aging philosopher, and it came from another reformer: Bl. Peter of Cluny, a leader of the Cluniac order (who like the Cistercians were a branch of the Benedictine family). Peter convinced Abelard to remain at Cluny, convinced the Pope to lift all the punishments (including the excommunication) as long as Abelard was under Peter’s eye, and even convinced Bernard to reconcile with Abelard.

Finally, there is one other thing Abelard devoted part of his energies to: composing poems, hymns, and laments. Just one survives with not only its words but the melody he composed for it intact: O Quanta Qualia, a meditation on the bliss and peace of heaven. This version (sung by Iranian musician Azam Ali) is a classic.

*This is the infamous split of 1054, which remains unrepaired. Several large-scale efforts at reconciliation have borne limited fruit, but the list of doctrinal, institutional, and cultural obstacles to reunion is formidable, and has only gotten longer. When Abelard was born, the split was only twenty-five years old, and prior schisms had lasted longer before being overcome.

**A canon here is a cleric (usually a priest) living in community with other clergy according to a set rule of life. They could be monastics, but did not have to be; non-monastic canons were sometimes called “secular canons.”

†Pronounced hell-oh-eez; the variant Heloisa (hell-oh-eez-ah) is sometimes seen. (Both are related to the more modern name Louise.)

‡It was a different time. But the astrolabe was a remarkable piece of technology, then thought to be an exotic new invention from Persia (though in truth its origins were older).

Gabriel Blanchard has a degree in Classics from the University of Maryland at College Park, and is CLT’s editor at large. He lives in Baltimore, MD.

If you enjoyed this piece, you might also like our seminar series, Journey Through the Author Bank, or our ongoing blog series on the Great Conversation. Thank you for reading the Journal.

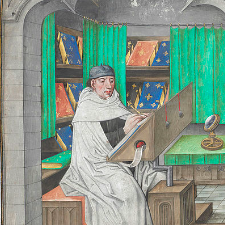

Published on 1st May, 2023. Page image of an illumination depicting Abelard and Héloïse, from a fourteenth-century manuscript copy of the celebrated allegory The Romance of the Rose, a seminal work in the tradition of courtly love. Post updated on 20th February, 2025, chiefly to add biographical information.