Texts in Context:

The Song of the Desert

By Gabriel Blanchard

The defining institution of antiquity had been the forum; that of early modernity would, perhaps, be a school. The path from the one to the other ran through a cloister.

Out of Egypt

We have profiled both St. Benedict of Nursia (480-547) and St. Gregory the Great (ca. 540-604) before. We have said little about the force which shaped them, and the Irish missionaries of last week’s post—namely, monasticism. To do so, we must rewind a few centuries, until, late in the 200s, we come upon a gaunt figure standing alone in the Egyptian wastes: St. Anthony the Great.

There were Christian ascetics before St. Anthony; to some extent, St. John the Baptist would appear to fit the bill. However, we know comparatively little about Anthony’s predecessors. What we know about him comes chiefly from a biography written by his younger contemporary and (from 328) bishop, St. Athanasius, and is as follows. He was orphaned at about twenty, in the year 271 or thereabouts; he sold his family’s property, gave the proceeds to the poor, and began his lifelong habit of living in the Egyptian desert, dedicating himself to fasting, praying, and vigils (i.e. going without sleep). He was reputed to do battle with demons and phantasms in the wilderness. Despite his efforts to avoid people, a community of aspiring hermits slowly coalesced not far from him; around the year 305, he finally assented to their pleas to guide them. In this way, the Nitrian Desert (immediately west of the Nile Delta) became one of the most important centers of primitive Christian monasticism. As the Great Persecution waxed hot, Anthony was known to come back to civilization to visit those in prison—this, at least, he did not do secretively. The Nitrian monks also received Athanasius during some of his exiles. At last, in 356, at over a hundred years of age, Anthony died. He left nothing in his will but two sheepskin cloaks—one to his disciple Serapion, the other to Athanasius.

Communities in and around Nitria persisted. It is thanks to them that we possess the treasury of ascetic theology known as the Apophthegmata,1 or Sayings of the Desert Fathers. Many of their sayings, whether because the context is lost or because they are “out of our league,” are baffling now:

Abba2 Lot went to see Abba Joseph and said to him, “Abba, as far as I can … I fast a little, I pray and meditate, I live in peace, and as far as I can I purify my thoughts. What else can I do?” Then the old man stood up and stretched his hands towards heaven. His fingers became like ten lamps of fire and he said to him, “If you will, you can become all flame.”

Others are as clear, and biting, as they were then:

[Abba Anthony] also said, “Our life and our death is with our neighbor. If we gain our brother, we have gained God, but if we scandalize our brother, we have sinned against Christ.”

The Lonely Ones

Monks soon became an admired class among Christians—the “Olympic athletes” of the spiritual. The word “monk” is derived from the Greek adjective μοναχός [monachos], meaning “solitary” or “single,” but many varieties developed.

Hermits and anchorites3 lived alone. Hermits took to the wilderness; anchorites might remain settled places, but would be confined to a single room, usually one adjoining a church. For a time, there was a vogue for imitating St. Symeon Stylites (c. 390-459), who lived for thirty-six years on a small platform atop a pillar; or rather, a series of increasingly tall pillars, for a reason St. Anthony would have found familiar. It does appear to be a fact, if odd, that humans are ravenously curious about—almost, it may seems, indignant at—anybody who chooses to withdraw quietly from the immediate stream of sense experience. (Any who doubt this are cordially invited by the present author to try the simple expedient of reading a book in public, and counting the minutes until some “well-socialized” individual attempts to pull them forcibly back into the stream by saying something like “Must be a good book!”)

Then there were cenobites, or “common-livers” (from the Latin coenobītæ, from the Greek κοινόβιος [koinobios], “common life”). These are monks in the sense we usually think of, communities under abbots.2 It was in the cenobitic form that St. John Cassian helped introduce monasticism to the West Roman Empire; St. Augustine was part of such a community before his election as a bishop. The British Isles in the Dark Ages knew both solitaries of the eremitic and anchoritic type, and large cenobitic communities. Ireland, uniquely, developed a custom of having “double monasteries,” one housing men and the other women, both overseen by a single abbot (or abbess, as the case might be).

There was also a class of wandering ascetics—at least, they regarded themselves as ascetics. One of their enemies gave them the unflattering name of gyrovagi, “gyrovagues” (meaning “those who wander in circles”); thanks to this foe’s influence, they eventually became extinct in the west. It was on their account that, in these earlier days of monasticism, the three vows associated with monastic life were not poverty, chastity, and obedience, but poverty, stability, and obedience. But let us turn to this influential monk.

The climate in which monastic prayer flows is that of the desert, where the comfort of man is absent, where the secure routines of man's city offer no support, and where prayer must be sustained by God in the purity of faith. ... Alleluia is the song of the desert.

Thomas Merton, Contemplative Prayer, ch. I

Saint Benedict

Like Anthony, Benedict did not set out to be famous, or even to found an order. Moreover, his Rule, though most of us would find it severe enough to live by, presents a striking contrast to the austere discipline of both the Egyptians and the Irish.4 Benedict emphasized that his Rule was for beginners on the way of holiness, and advised not only humility in the sense of obedience to one’s abbot, but in the sense of realism about one’s own capacities. In other words, don’t begin by trying to fast for a week; begin by fasting for one day, and work from there.

Benedict began as a hermit; but, like other hermits, he was not left in peace. A freshly abbot-less community asked him to become their head: he tried to demur, arguing that their ways of living were too dissimilar, but they would not listen, so he accepted the post. Why they wanted him so badly can only be put down to the prestige of his name, since, according to later accounts, it wasn’t long before the monks were trying to poison their new abbot. He was allegedly saved miraculously—the poisoned cup spontaneously broke when he blessed it. Nonetheless, St. Benedict carried on, founding houses in the countryside of central and southern Italy even as the remains of imperial power crumbled. He died in the mid-sixth century; the Benedictines went on to become the most influential monastic family in the Latin Church, with many offshoots and reforms (such as the Cistercians, Cluniacs, Trappists, and even the Knights Templar).

Servus Servōrum Deī

Benedict’s most celebrated biographer was born right around the year he died. The Anicii were a respected plebeian family of Rome (one Gaius Anicius is recorded as a friend of Cicero); they had given sons to both state and church, Boëthius not least among them. Gregory had already been the prefect of Rome and retired from that role to become a Benedictine monk when Pope Pelagius II chose him as his ambassador in New Rome, at almost fifty years of age, even though Gregory could not speak Greek!5 When he returned, he wanted to go on a mission to the Angles,6 but the Roman populace would not be deprived of him.

In 590, when Pelagius, died, Gregory was promptly elected pope, over his own objections. Though he still grieved the loss of his monastic peace, he proved one of the most intelligent and effective occupants the Chair of Peter has ever had—he was the first pope to use the title servus servōrum Deī, “servant of the servants of God,” and to all appearances, he meant it. Italy had practically been laid waste by the Lombards. Rome lay within a thin strip of land known as the Exarchate of Ravenna; it was nominally subject to the emperor in New Rome (hundreds of miles to the east), but he neglected its people almost completely. Gregory, who was not only driven by charity but understood administration and finance, transfigured the clergy and staff of his see into an effective distributor of food to the entire city: he organized agricultural lands held by the church, set production quotas to keep the people fed, eliminated clergy and officials who proved corrupt or slothful in their care for the destitute, assigned priests and monks to track down people who were unable to come and collect the food that was being distributed—distributed, by the way, for free. Nearly a thousand years later, even as avowed an enemy of the papacy as John Calvin said flatly that St. Gregory the Great was the last of the good popes.

He never did get to go on that mission to the kingdoms of the Angles. However, he did get to commission a man now known as St. Austin7 to go in his stead on what was thereafter called the Gregorian mission; in 597, St. Austin became the first bishop of the city of Cantuaria, or, in modern English, Canterbury.

1Pronounced à-pŏf-thĕg-mä-tà or ă-pø-thā-mä-tà (underlining indicates secondary accent); both spelling and pronunciation are why most English speakers use “Sayings of the Desert Fathers” instead.

2This is derived ultimately from the Aramaic word אַבָּא [‘abbā’], “father.”

3Or in the feminine, anchoresses. Dame Julian of Norwich was an anchoress, and in fact takes her “name” from the Church of St. Julian, to which her cell was attached (her own name has been lost).

4For instance, the Rule of St. Columba allows monks to pray and work until these activities make them sweat—as a concession, since not everyone can pray and work until they break down in tears.

5This was not as crippling as it may sound: Latin was still the official language of the East Roman Empire (the change to Greek was not made until the reign of Heraclius [610-641]), so translators would be easy to come by.

6The story that, on seeing some Angles for the first time and being moved by their blue eyes and golden hair, St. Gregory said these Anglī should rather be called angelī (angels), appears to be well-founded—confirming once and for all that clergymen have always been like this.

7Augustine was the original form of his name; “Austin” is a slightly worn-down English adaptation. However, it is useful to be able so easily to distinguish him from the other St. Augustine.

An uncle to seven nephews, Gabriel Blanchard has a degree in Classics from the University of Maryland, College Park, and serves as CLT’s editor at large. He lives in Baltimore, MD.

If you enjoyed this piece, you might also like some of our introductions to the great writers of the Middle Ages and their works, such as The Thousand Nights and a Night, Peter Abelard, Marie de France, and Christine de Pizan. For a look at some of the ideas that were foremost in their minds, consider these essays on logic, romantic love, Scripture, and the problem of universals. Thank you for reading the Journal.

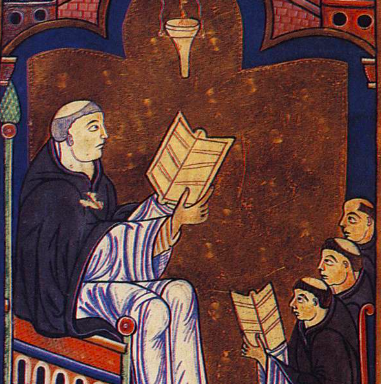

Published on 18th November, 2024. Quotations from the Sayings of the Desert Fathers come from the translation of Benedicta Ward, S.L.G, from Cistercian Publications. Page image of a pair of leaves from the Morgan Black Hours; “black hours” were illuminated books of hours (i.e., daily prayer-books) using a luxury type of vellum dyed a deep bluish black, typically with lettering in silver or gold. The region of Flanders (the north of modern Belgium—its inhabitants are called the Flemish) was known for creating these; the Morgan Black Hours were produced in Bruges in the mid-fifteenth century.