Wycliffe

An Author Profile

By Gabriel Blanchard

In one sense Wycliffe was simply one more example of Medieval patterns of belief and devotion; but the patterns were breaking, and would soon shatter irrecoverably.

If you ever acquire a time machine, gentle reader, and decide to take it for an edifying trip through history, a word to the wise: fourteenth-century Europe is not a recommended destination. The late Middle Ages were polluted with every kind of problem, small and great. However, the most infamous were three: the first phase of the Hundred Years’ War (1337-1360), the outbreak of the Black Death (1346-1353), and the “Babylonian captivity” of the papacy (1309-1376).* The Hundred Years’ War was a dynastic dispute between England and France over the throne of the latter; it was one of the longest wars in history, spreading to many countries besides its originators (and not only failing to win England sovereignty over France, but contributing to a dynastic war in England shortly afterwards. The Black Death had visited Europe before, in Justinian’s time, but in the intervening centuries either immunity had faded or a new strain of the bacterium had evolved: estimates vary, but the lower ones range around seventy-five million people, a third of the European populace at the time. And finally there is the “Babylonian captivity”: for nearly seventy years, the seat of the papacy was moved from Rome to a city called Avignon in southern France. The whole papal court was heavily dominated by the French at this time—and also, incidentally, infamous for corruptions to rival the worst of the Renaissance Popes. (Dante was not alone in his outspoken hatred for the avarice and corruption of the Church in his time.) It is arguable that, between them, these three events finally ended the Middle Ages.

It was into this century, rife with unrest and want, that John Wycliffe was born. He was from Yorkshire, in the north of England; at some point (it is known that it was before the Black Death), he traveled to Oxford to join the university, where he became a lecturer and later a priest. While there, he published his first book, The Last Age of the Church. This work declared that the world was shortly to end—isn’t it always—and interpreted the recent plague not as a judgment upon sinners generally, the way most people viewed it, but specifically as a condemnation of an unworthy and hypocritical priesthood. His next several books were on more academic matters, typical of his field; it is traditionally said that it was also in this period that he began to work on his English translation of the Bible.**

Things started to change when in 1377, in his mid-fifties, he branched out into politics with De Civili Dominio (“On State Ownership”). Wycliffe argued that the state, here the English crown, ought to expropriate the property of the Church and that all clergy should devote themselves to poverty, not least as a concrete act of repentance for their sins. He also asserted that the institutions of monasticism were hopelessly corrupt and should be abolished. Since we all know that monastics take their special three vows, one of which is poverty, this may appear strange or nonsensical; surely that ought to make them his ally? But since the members of religious orders practiced individual poverty, it was nonetheless possible for them as an order to possess fabulous wealth, and many did, often with the power to match. Wycliffe even appointed advocates, whom he called “poor priests” (although most were laymen), to bring his message all over the country.

Shockingly, his fellow Catholic clergy and especially his ecclesiastical superiors were thrilled by none of this, and Wycliffe was soon being summoned to explain what he was on about to the Bishop of London. At this point, he was not yet being formally examined for heresy. His advocacy of reform, especially clerical poverty, had won him popularity with many people in England, notably the powerful noble John of Gaunt. In criticizing the Church’s corruption, Wycliffe had near-unanimous support (even if some of the unanimity was hypocritical); in criticizing not only the corruption of the Church but the autonomy, legal power, and wealth which facilitated that corruption, support was bound to be patchier yet still substantial.

Crown and cloth maken no priest, nor emperor's bishop with his words, but power that Crist giveth; and thus by life have been priests known.

John Wycliffe

But in 1381, he set forth his definition of the Eucharist, dismissing transubstantiation. This furnished the clergy with far more power to act in his case, and incurred the danger of excommunication for Wycliffe (which would effect not only widespread ostracism but deprive him of his living as a priest). To this he argued that Scripture was the only real source of authority in Christianity: priests and bishops might be good, but they were good as helpers with Scripture, not replacements. He also continued to argue that the state ought to play a substantial role in the reform of the Church, which endeared him rather to parliament and the crown.

In the same year, a rebellion took place known as the Peasants’ Revolt, a connected group of uprisings all over England in protest against high taxes, the state of serfdom, and the power of some of King Richard II’s favored counselors. Several of these were killed by the rebels, including Simon Sudbury, the Archbishop of Canterbury. Wycliffe did not approve of the Peasants’ Revolt (which was in any case put down by the young king with unusual deftness), but it had drawn vigor from the “poor priests,” who spoke words of fire against the wealthy nobility as well as the clergy. Given the obvious egalitarian tendencies of Wycliffe’s theology, it is striking that the chanted slogan of the Revolt was When Adam delved and Eve span, who was then the Gentleman?†

A synod was called the following spring at London to deal with Wycliffe; ten doctrines attributed to him were condemned as heresies. Nevertheless, perhaps thanks to his continued high standing with the government, Wycliffe was not excommunicated or even removed from his ecclesiastical position. In his last few years (he died at the end of 1384), he continued to write and develop his views, incorporating still more elements that the Catholic Church had already anathematized—most importantly, the well-known Donatist heresy, which asserted that priests who lived wickedly thereby invalidated their own priesthood and therefore also the sacraments they offered.

Wycliffe left behind him the Lollard movement, an underground dissident group that disseminated and studied his English translation of the Bible, advocated a life of poverty for all Christians and especially all clergy, and broadly rejected the Catholic priesthood and its sacraments.

In some ways, this was all very unoriginal (which, to be clear, need be no insult—as Wycliffe might have retorted, it is not the business of historians or theologians to be original but to be truthful). Lollardy was, in its day, the latest in a long tradition of what might be called the Medieval poverty sects. Going back to the eleventh century, these were mainly popular movements that demanded reform and purity in the clergy, including the imposition of poverty; the Franciscan Order was arguably an attempt to both give voice to and satisfy these instincts within the bounds of Catholic orthodoxy, since most of the Medieval poverty sects also had unorthodox or millenarian views. Wycliffe and his disciples closely reproduced the views of the French Waldenses and Italian Umiliati, which had arisen in the twelfth century, and in Wycliffe’s own wake we find figures like Jan Hus and the Moravian Church, which would in turn influence the Protestant Reformers. Wycliffe thus stands in a curious historical position, neither concluding the dynasty of Christendom’s discontents, nor founding it, but quietly linking things startlingly unlike, such as St. Francis and Martin Luther.

*Many historians believe the famines and plague were caused by the close of the Medieval Warm Period, an age of unusually warm weather in the North Atlantic from the mid-tenth century to the beginning or middle of the thirteenth. (The Norse colonies in Greenland were established during the MWP, as the island was more hospitable at the time). After this came the “Little Ice Age,” lasting about from the end of the MWP until the Victorian era.

**Contrary to widespread belief, it was not forbidden to translate the Bible into the vernacular in the Middle Ages, nor was it placed on the Index of Forbidden Books (indeed, the Index did not yet exist). That said, there was immense reluctance on the part of the hierarchy to pursue, or even accept, vernacular translations of either the Bible or the liturgy for other reasons, largely the fear of their being warped and misused by preachers without sufficient education.

†This is in a Middle rather than Modern English idiom; Adam and Eve are of course our first parents in Genesis; delved and span refer to digging (in order to mine, farm, build, etc.) and spinning thread, the typical gendered occupations of lower-class men and women at the time. Gentleman at this period had little to no connotations of refinement, manners, or ethics, but meant simply “a member of the gentry, a noble.”

__________________________________________________________________________________

Gabriel Blanchard is CLT’s editor at large. He lives in Baltimore.

If you enjoyed this piece, take a look at some of our other material, like these author profiles of Seneca the Younger and George Orwell, this student essay on applying Biblical principles to the US prison system, or these Great Conversation posts on the ideas of faith and, for that matter, ideas. Thanks for reading, and have a great day!

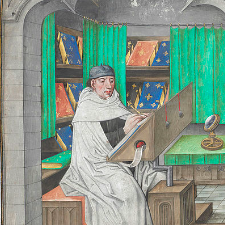

Published on 30th January, 2023. Page image of Merton College Chapel, Oxford, photographed by Ozeye (source); some of the church’s original stained glass (dating to 1294) survives, meaning that some of these windows may have heard Wycliffe’s sermons.