Sorting Through Sophistries:

Appeals to Emotion (Aren't Always Bad)

By Gabriel Blanchard

Like poisoning the well or the fallacy fallacy,* we have here a set of ambivalent sophistries; they lack commitment to being sophistical.

The Verdicts of Passions

Appeals to emotion occupy a slightly difficult place in the broader world of fallacies. As a rule, the root logical problem with every kind of fallacy is irrelevance—in that way, the red herring is the prototype of every fallacy. They always divert attention in some way from the point under discussion. When the sophistical Mr. Y straw-mans Miss B’s position, he distracts us from her real position, just as when he makes a motte-and-bailey with his arguments, he distracts us from his own. Even invalid inferences work this way, seeming to present a connection between two statements when that connection does not really exist.

In this way, it’s easy enough to see how strong emotions can serve sophistical causes. Emotions—and especially the more urgent kind, the kind that call on us to translate them into prompt action, like fear, craving, or anger—do not go well with the word deliberate, whether it’s being used as an adjective or as a verb. The adjective means “intentional, ‘on purpose’,” but emotions are more like something that happens to us than something we do; the verb means “take thought for, consider,” and even “discuss,” but emotions tend to be of the opinion that “the time for half measures and talk is over.”** They tend to prefer judgment, and the power of decision that comes with it, to deliberation; indeed, they often urge judgment at the expense of any analysis of the facts.

The Counsels of Oratory

But therein lies another part of the problem. The phrase “getting in your own head about something” exists for a reason! As do emotions. They differ from the intellect, because they do a fundamentally different job from the intellect, so to speak. Even Aristotle—one of the greatest champions of the supremacy of intellect who ever put pen to papyrus—believed that whereas the mind should rule the body like a tyrant, it ought to rule the heart like a constitutional monarch. His works on logic, known collectively as the Organon (meaning “the Toolbox”), are justly celebrated, but he himself said that logic alone was not enough to convince most people of truth. The art of persuasion, a.k.a. rhetoric, was also necessary; and, though the Sophists might have given rhetoric a bad name by resorting to deceptive tactics, Aristotle maintained that it was possible and indeed a great good to practice the art of persuasion honestly. In his book on rhetoric (handily titled Rhetoric), he taught that there are three sources of persuasion: ēthos [ἦθος], or the appeal to personal credibility and character; pathos [πάθος], or the appeal to the emotions; and logos [λόγος], the appeal to rationality. Not one or two of these, but all three, had their appropriate uses in his eyes.

In other words, while he was half-right, Bertrand Russell was only half-right when he said this:

The degree of one's emotions varies inversely with one's knowledge of the facts: the less you know the hotter you get.

Bertrand Russell

It is, of course, true that personal attachment to such-and-such a belief often emerges in advance of the evidence, and can result in confirmation bias or even motivated reasoning (the polite, psychological term for “deciding something is true because you wish it to be”). But there is a catch here that Russell did not see; it was expressed well by C. S. Lewis in his Preface to “Paradise Lost”:

Certain things, if not seen as lovely or detestable, are not being correctly seen at all. When we try to rouse someone’s hate of toothache in order to persuade him to ring up the dentist, this is rhetoric; but even if there were no practical issue involved, even if we only wanted to convey the reality of toothache for some speculative purpose or for its own sake, we should still have failed if the idea produced in our friend’s mind did not include the hatefulness of toothache.

In other words, there are times when it is, far from being fallacious, appropriate to appeal to a person’s anger, or pity, or fear, or sense of humor, and so on. We ought to be outraged by injustice. We should feel compassion for the destitute. It is wise to be afraid of jumping into the crocodile enclosure at the zoo. The humorless person is at a disadvantage in life. Honesty and impartiality are worthy goals—but “objectivity,” although much-touted in some circles, is not just humanly unattainable: it is undesirable. This makes sense, really. To treat the world as if it were composed entirely of objects when we know that it contains subjects, like ourselves, is illogical.

Appeal to the Irish Goodbye

Having now contextualized the emotional fallacies, we shall of course say nothing further about them. That, gentle reader, is for next week

*For those who may be unfamiliar with either one, we addressed poisoning the well in a post from April of this year, and the fallacy fallacy in our post of two weeks back.

**The film you’re now suddenly thinking of but can’t place is 2000’s Gladiator, directed by Ridley Scott.

Gabriel Blanchard was classically educated, and received a degree in Classics from the University of Maryland, College Park. He lives in Baltimore, MD.

We hope you’ve enjoyed reading the Journal. The whole of our “Sorting Through Sophistries” series (updates on Thursdays!) is dedicated to examining informal fallacies and teaching our readers how to spot them. You might also enjoy our past series on “the Great Conversation,” which dealt with topics ranging from angels to games to mathematics to monarchy to revolution, and many more. And don’t forget to tune in to Anchored, the official CLT podcast.

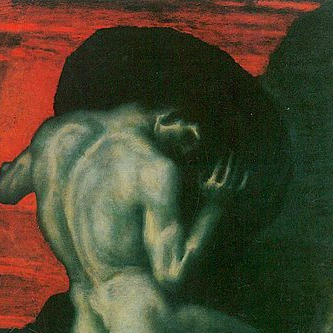

Published on 25th July, 2024. Page image of Das Eismeer (“The Sea of Ice”), 1824, by Caspar David Friedrich, one of the earlier Romantic painters. Friedrich’s focus on nature in this painting—at the expense of the wrecked ship visible on the right, the only human element in the tableau—was unusual and striking in the early nineteenth century; this shift in focus became characteristic of Romantic art.