Texts in Context:

Blood Upon the Roses

By Gabriel Blanchard

O quam cito transit gloria mundi, "Ah! how quickly hath the world's glory departed," wrote St. Thomas à Kempis—a perennial lament, and as perennially, a warning ...

Behold, a Red Horse

The fourteenth and fifteenth centuries were a hard time in England—and elsewhere. The Black Death was continent-wide; and while much of the misery of these centuries was thanks to a series of six wars that all revolved around the English crown, the first five were mostly fought on Scottish and French soil. In chronological order, these were:

- the First Scottish War for Independence (1296-1314)—this is the good one that’s got a Sir William Wallace and a King Robert the Bruce in.

- the Second Scottish War for Independence (1332-1357)—a weak excuse to bring back characters flimsily linked to the background of the first.

- the Edwardian War (1337-1360)—pretty much What It Says On The Tin, but features some genuinely moving moments (see below).

- the Caroline War (1369-1389)—the boring middle; no one cares.

- the Lancastrian War (1415-1453)—features some of England’s most famous victories (e.g. Agincourt1), yet they lost, so, points for irony.

The last three are usually lumped in with a French conflict (the Armagnac2-Burgundian Civil War of 1407-1435), and these collectively are called the Hundred Years’ War. Canny readers may notice that the gap between 1337 and 1453 is greater than one hundred years; those cannier still that, due to the gaps between the different phases of the war, its total comes to rather less than one hundred years. Mathematics is baffled.3

The Lion and the Lily

It began as a succession dispute. King Charles IV of France died childless in 1328; Edward III of England, his nephew (and still the lord of substantial territories in France, including Aquitaine, making him a subject of the French crown as well as the monarch of a foreign state … Medieval law was complicated), put forward a claim to the throne. This was rejected, on the ground that French law did not allow inheritance through the maternal line; then, after nine years and a lot of gossipy complications, England raised its red standard with its three golden lions and tried to conquer France.

It nearly succeeded in taking down that blue flag, scattered with the golden lilies of the Virgin; but, importantly for European and world history, it did not. Say what one will about St. Joan of Arc—and historians do seem to really love saying whatever they personally will about St. Joan of Arc—but her mission did succeed: Charles VII was duly crowned King of France in 1429, and French independence thereafter remained secure (though the kings and queens of England continued to quarter the French coat of arms with their own, a symbolic claim to the throne, all the way down to the reign of Queen Anne).

Alas, that is all the summary of the Hundred Years’ War we have time for—well, plus this episode from the period between the Edwardian and Caroline Wars. For four years (1356-1360), King John II of France was held for ransom by the English, and was permitted to return to France to raise the money only by leaving his son behind as hostage in his stead.4 Three years later, hearing his son had escaped, John determined to return to England as their hostage, merely for the sake of making good on his word. His council, obviously, urged against this; but he rejoined: “If good faith were banned from the earth, she ought to find asylum in the hearts of kings.” He returned to England, and there he died.

The Roots of the Roses

But what of the sixth war that troubled England in the Late Middle Ages? It too was a series of conflicts treated as one, and it too was a dynastic dispute; but it was fought on English soil. We can only summarize of the Wars of the Roses, but we can at least keep true to form by first blaming it on Edward III.

Which is funny, because Edward III was a pretty successful king. Not only was he a competent general, but—and this blessing seems sadly rare among royal families in the Middle Ages—he and his wife seem to have respected and liked one another. They had five sons who lived to adulthood, which was a rare feat then too; four of them were ancestors of future kings of England: Edward “the Black Prince,” Lionel of Antwerp, John of Gaunt, and Edmund of Langley (all of‘d for their birthplaces—Gaunt was the Middle English name for Ghent, which like Antwerp is in Belgium). The Black Prince, Edward’s eldest, was chivalrous, smart, and popular, and would by all accounts have made an excellent king, but this obliged him to die young for narrative purposes. However, he lived long enough to have a son of his own, and since his was the senior line of succession among his brothers, Edward III was succeeded by his grandson Richard II, who took power in 1377 at the age of ten.

At first, Richard reigned fairly well—allowing for the fact that he was literally a child. In 1381, the Peasants’ Revolt occurred, a collection of uprisings mainly in the east and southeast of the country (places like Cambridge, Essex, Kent, Norfolk, and London itself), with related or parallel explosions as far afield as Ilchester, Leicester,5 Worcester,6 and York.7 It had many causes, but was provoked by high taxes and unpopular royal advisers. The London group, led by a peasant and a priest, Wat Tyler and John Ball, were famous for their (admittedly very catchy) slogan: When Adam delved and Eve span, who was then the gentleman?8 Despite his inexperience and the immense danger to himself, Richard put the revolt down swiftly, and with astonishingly little loss of life. As for more peaceful domestic affairs, both His Majesty and his uncle John of Gaunt (the wealthiest man in England, and through his second wife a pretender9 to the throne of Castile) were great patrons of the arts, particularly of a poet from a well-to-do family of wine-merchants, one Geoffrey Chaucer.

But with time, the young king became increasingly autocratic and vindictive; among other things, he banished John of Gaunt and his son, Henry of Bolingbroke (who had narrowly escaped death himself during the Peasants’ Revolt). But on his father’s death in 1399, in defiance of Richard, Bolingbroke returned to claim his inheritance. The country wavered, and then solidified behind him; Richard II was deposed and imprisoned in Pontefract Castle in western Yorkshire; by the middle of February the following year, he was dead. Since Richard had no children and Bolingbroke was also a grandchild of Edward III, he thus became King Henry IV; being, however, descended from a younger son of Edward’s, his lineage was a cadet branch of the Plantagenets, known as the House of Lancaster. (In imitation of the golden rose used as a badge by Edward I, Edward III’s own grandfather, this house would later be symbolized by a red rose.) Of this house came King Henry V, of Shakespearean fame. He almost effected the conquest of France, but narrowly missed it by dying in 1422, while the French king he was supposed to be the heir to was still alive.

Painting the Roses White

Henry V had a son, who was duly proclaimed King Henry VI; but all this time, there had been a catch.

Ye lust, and have not: ye kill, and desire to have, and cannot obtain: ye fight and war, yet ye have not.

James 4:2

Henry IV had been the son of John of Gaunt, who was the third son of Edward III, yes. But what about Lionel of Antwerp, who as the second son had a line of descent superior to John’s? He had a daughter, Philippa. True, daughters at this time were normally passed over in favor of sons. But the whole basis of England’s claim to the throne of France, which the Lancastrians were so committed to that the final phase of the Hundred Years’ War is named for them, was that inheritance through the female line was valid. Which meant that by law, the English crown ought to be resting on the head of, let’s see … well here’s a funny coincidence! The senior claimant from this line of descent would be Lionel’s great-great-grandson, another Richard, this time of York. It so happened that, if one chose to trace Edmund of Langely’s descendants, one would also come across a Richard of York—the same Richard of York, who was thus of royal blood on both sides, and of the senior lineage on his mother’s. This lineage would be known henceforward as the House of York, whose badge was a white rose.

Even so, Richard might never have tried to make good on his formidable claim to the throne; he served the Lancastrian monarchy, to all appearances, contentedly enough for some time. But Henry VI possessed an anxious, self-effacing temperament quite unlike his father and grandfather (or even Richard II, for that matter). He was a useless king. Besides having bouts of catatonia, one of which lasted over a year, he presided over a failed attempt to conclude the Hundred Years’ War that resulted in the loss of nearly all of England’s territory in France, an unheard-of and incomparable disgrace. He had somehow contrived to snatch defeat from the jaws of his father’s victory.

In May of 1455, sick of Henry’s incompetent and erratic government, Richard Plantagenet, the Third Duke of York, raised his pennons in revolt to claim the crown. There is little point in going over the numberless feuds, reversals, and treacheries of the Wars of the Roses, which were waged off and on for thirty years. A darkly amusing detail from them, which rather gives the idea, is that the Yorkist-Lancastrian conflict was inflamed by and reflected in the rivalry of the Percy and Neville families of Yorkshire—so much so that when the Nevilles switched loyalty from the white rose to the red, the Percies couldn’t bear to be on the same side as the Nevilles, and became Yorkists! Richard’s insurgency was not a success for him personally, but his cause eventually won crown for his eldest son in 1461, who took the throne as Edward IV. So that was over.

By Thorn-Bound Thicket Branches to the Throne

Except, the Lancastrians didn’t just give up. In 1470, they overthrew Edward IV and restored the rightful monarch, Henry the Sixth Plantagenet, by the Grace of God King of England and France. The Yorkists, now feeling left out of the “restoration” fashion, did the same thing—but rather than look like copycats, they tastefully waited until 1471 to reclaim the crown for the rightful monarch, Edward the Fourth Plantagenet, by the Grace of God King of England and France. With this, the officially Plantagenet-in-the-strict-sense infighting concludes—well, maybe, but … Medieval law-breaking was even more complicated.

Thanks to some kind of intrigue (on whose part is not agreed among historians10), he was succeeded by his brother, Richard III. But it was barely two years from Richard’s accession until the Battle of Bosworth Field in 1485. There, England’s last monarch of House Plantagenet was killed; and talking of dark ironies, it was either treachery or indecision on the part of a Percy (Henry, the fourth Earl of Northumberland) that helped lose his side the battle.

The winner also happened to be a Henry. He brought a new dynasty to power: a Welsh family,11 the Tudors. They were descended from a natural son12 of John of Gaunt; accordingly, the Tudor (let’s be generous) claim to the throne came in on the Lancastrian side. Still, even King Henry VII listed de jure belli, “by right of conquest,” before de jure Lancastriæ, “by right of Lancastrian blood,” in his own assertion of his right to the crown. He also made the mollifying decision to marry the eldest daughter of the late Edward IV, which united the Yorkist and Lancastrian claims—a unity symbolized in the Tudor rose, which has a white Yorkist rose nestled in the heart of a red Lancastrian one. Henry VII also made the union of claims even stronger by getting rid of as many other Yorkists as he could, not infrequently by judicial murder.

The present author hasn’t got the faintest idea what the moral of all that is. But it is how the Wars of the Roses ended.

1Pronounced ä-zhĭŋ-kûŕ or ä-zhĭŋ-kõŕ; this battle took place in 1415, and is the one before which the play’s title character gives the celebrated “St. Crispin’s Day” speech in Henry V.

2Pronounced äŕ-män-yäk. The Armagnacs were supporters of the House of Valois (väł-wä), a cadet branch of the House of Capet (kà-pā), kings of France since the reign of Hugh Capet (887-896); their rivals, the House of Burgundy, were in turn cadets of the Valois. The Burgundians, whose more-urban land lay in the Lotharingian corridor (where the Low Countries and Switzerland are now), made a living largely from the textile trade—which meant they relied on English wool, and so wanted peace with England. By contrast, the Armagnacs had a strong agricultural base, on whose land England fought most of the battles of the Hundred Years’ War.

3It must be allowed that “the Eighty-Seven Years’ Intermittent War” really hasn’t got the same ring to it.

4This may sound cruel at first, but being a hostage back then wasn’t at all bad if you were a royal. Even a hostage prince was still first of all a prince, and had to be treated a certain way: He couldn’t come try on the other prince’s crown or anything, but he would be provided with comfortable quarters, a well-laid table, and at least a small personal staff (valet, maid, chaplain, physician if needed) to attend to him, all suited to his rank; and this was only the baseline.

5Pronounced lĕs-tŕ.

6Pronounced wüs-tŕ.

7Pronounced yõŕk.

8In this context, “gentleman” means a member of the aristocracy (a.k.a. the gent-ry).

9“Pretender” is a technical term in monarchist political science, with no negative connotation; it simply means “claimant” (normally to a crown). Thus, when Queen Anne described her half-brother James (who asserted he was by right king of Great Britain and Ireland) as “the pretender,” she was if anything being circumspectly neutral, not insulting. Had she wished to insult, she could instead have called him “the false pretender.”

10Defenders of King Richard III (who do not accept the theory that he had his nephews, the two sons of Edward IV, murdered) generally accept the bill Titulus Regius, according to which Edward was a bigamist, rendering his children illegitimate. Other historians believe that Titulus Regius was a fraudulent bill, and that Richard usurped the throne and assassinated his nephews to secure his position; this was the accepted narrative under the Tudors, but began to be challenged in the seventeenth century.

11Though of course no longer associated with the throne, the Tudor (or Tudur) family still has descendants, some of whom continue the surname.

12“All children are natural, but some are more natural than others and are therefore known as natural children.” —Will Cuppy, The Decline and Fall of Practically Everybody.

Gabriel Blanchard is CLT’s editor at large. He died in battle in Baltimore, MD in 1485.

If you enjoyed this piece, you can find more of our Texts in Context series at the link. You might also enjoy our podcast, Anchored, hosted by CLT founder Jeremy Tate—check it out!

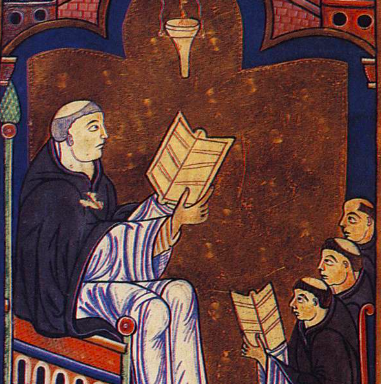

Published on 2nd June, 2025. Page image of Plucking the Red and White Roses in the Old Temple Gardens (1910) by Henry Payne, depicting a scene from Shakespeare’s play The First Part of Henry the Sixth, a.k.a Henry VI, Part 1; this play, the first of a trilogy, depicts the loss of the tremendous gains in France achieved by King Henry V, and the nobles of England taking sides against each other. The division is symbolized in the play by nobles picking roses of different colors (though this is not, and probably was never meant to be, historical). This post was updated on 15th July, 2025, with minor changes and corrections in wording and punctuation that do not substantively affect meaning.