Texts in Context:

The Realignment of the Eighth Century

By Gabriel Blanchard

The Roman Empire—not as a concrete state, but as an idea—was about to take on quite a different shape.

The Servant of the Merovingians

Two weeks ago, we spoke of the Umayyad Caliphate overwhelming Hispania and invading the south of Gaul. In the northernmost highlands of Hispania, Visigothic Christians clung to independence, establishing the Kingdom of Asturias, but for centuries, the rest of the Iberian peninsula was under Muslim control as the province of al-Ándalus.1 The aforementioned invasion of Gaul is the salient point: It was here, even more than at the First Fitna, that the histories of Islam and Europe alike turned a corner. By 719, they had taken Narbonne, their first claim beyond the Pyrenees, and over the next decade they continued making attacks and raids in the south of Gaul.

At this time, Gaul was mostly under the lordship of the Merovingian dynasty, i.e. the descendants of the Frankish chieftain Clovis (or in modern French, Louis2). Clovis had been the first important Gothic leader to convert to Catholicism rather than Arianism, and his realm had become quite substantial, embracing nearly all of modern France and Belgium and a good chunk of Germany. By about the year 730, Count Odo of Toulouse sent word to the Merovingians’ majordomo,3 an official named Charles, begging for help against assaults from the far side of the mountains. After getting an oath of fealty out of Odo, Charles proceeded to fulfill what were now his duties as Odo’s liege.

In October of 732, he met the Umayyads for the Battle of Tours. Charles was cunning, and the terrain was on his side; the Umayyad cavalry were used to the deserts of Africa and the chaparral of Hispania, not the damp woods of northern Europe. The real size and placement of the Frankish army was concealed among the trees—trees the Umayyads would have to maneuver around whenever they wanted to attack, which they had to charge uphill to do, since Charles kept his warriors on hilltops. Moreover, the Franks were dressed for the approaching winter. The Umayyads had probably thought they were too, but in the Mediterranean, winter primarily means storms—not airs so bitterly cold they could freeze running water! The outcome of the battle can doubtless be guessed. It was from this that majordomo Charles received his great epithet—no, no, not that one: This is Charles Martel, or “Charles the Hammer.” All the same, we aren’t far from the Charles you were thinking of. But first, let’s have a glance at …

Feudalism

Note: Several words in this section are underlined, to indicate that extra

info on them (including pronunciation) is given at the foot of this post.

Those mentions of the words “fealty” and a “liege” naturally raise the ghost of feudalism. Though the word is familiar, the system is not well understood by most people today; it was not really thought of at the time as a self-coherent system, nor deliberately designed to be such—certainly not in the way most modern nation-states have explicit constitutions that profess to guarantee self-government. Rather, it arose by custom piled on custom, and could be very local. Moreover, it held mostly in the countryside: cities were their own ball game, especially in places like northern Italy with a robust tradition of republicanism. But it is worth sketching a simplified version of the system for future reference.

The basic relation that defined feudalism (still taking shape in Gaul at this time) was one of military command, and had a structure rather like the Bronze Age covenants between a lord and his vassal. A lord received an oath of fealty from his vassal: this was a promise of reverent loyalty and support, usually in the form of soldiers and/or counsel at his lord’s request. In exchange, the lord granted him a fief, i.e. an agricultural estate, usually with certain families “attached” to it to work the land. Early on, in former Roman territories, this might mean the remains of a villa once owned by a Roman aristocrat, and the “attached” people were the estate’s slaves, or in Latin servī.

Up to the Spanish pass Roland is riding,

Galloping on his good steed Veillantif;

Well-armed is he, and pride is in his bearing:

Bravely he goes, hand up, his spear therein,

Its point against the skies is swiveling;

To it, a pure white banner he has pinn'd,

And to his hand flutters its golden fringe;

His limbs are noble and his face is smiling.The Song of Roland, stanza 915

The same individual might swear fealty to multiple lords, for different fiefs; in fact, this was common in the Middle Ages.4 Perhaps to resolve the contradictions this threatened, fealty could take the stricter form of homage, making the lord in question one’s liege or paramount lord, and oneself his homme, “his man”; homage could be given only to one person. Further, someone who had sworn fealty to a lord might in turn receive oaths of fealty from a lesser vassal, especially if his fief were particularly large (like Yorkshire in England). However, one of the wrinkles of the feudal system was, these oaths were not “transferrable.” Suppose the King of France has the Duke of Brittany as his vassal, so all the vassals of the Duke of Brittany are helping him help the King of France in a war. Now suppose the Duke of Brittany is killed in battle. By strict feudal rules, the men from Brittany can just go home. They didn’t swear homage to the King of France; their duke did that. This was a major obstacle to state centralization—which the reader may adjudge bad or good for themselves.

Another Renōvātiō Imperiī … ?

Charles Martel was succeeded by his son Pepin the Short; he need not detain us, save perhaps to note that he made the Donation of Pepin in 756, recasting central Italy as the territorial domain of the papacy itself—a complete novelty, which allowed the popes some security against the chaos of the age without relying on the distant, often indifferent, emperor in New Rome. Pepin was succeeded by his son Charles in 768, who set about making Francia one of the most illustrious states in European history. He subjected Lombardy, rather than merely trouncing it as his father had done; he did his grandfather one better, crossing into Iberia and establishing a march6 in the foothills of the Pyrenees; he reduced Saxony, Bavaria, and Carinthia; and, without outright conquest, he established lordship over Bohemia, Brittany, Croatia, Moravia, Pannonia, and more realms besides.

But Charles was interested in more than conquests, or converting the conquered to Christianity (and make no mistake: he was quite keen on both of those things). He summoned scholars from all over Western Europe to his court, especially the British Isles, from which came Alcuin of York, the most renowned scholar of his day. Under Alcuin’s supervision, Francia saw a cultural revival that has been justly termed the Carolingian Renaissance. Charles encouraged widespread literacy, and a new form of writing flourished with it: a neat, clear script called Carolingian minuscule, which was easier both to write and to read than the old cursive forms of Latin. We still feel the effects of the Carolingian Renaissance to this day: most of the manuscripts we possess that preserve the works of classical antiquity, from Homer to the New Testament, are copies that were made during the reign of Charles. Small wonder that he earned the title “Charles the Great,” usually given in its French form: Charlemagne.

The popes had had forty-four years to reflect since the Donation of Pepin. Byzantine civilization might be going strong in its own right, but it had been little concerned with Italy since Justinian‘s death, except to delay the confirmation of papal elections by demanding a say (and periodically succumbing to heresies that left the Church split for decades at a time). And the threat of the Muslim emirate in Hispania was not going away. If only there were a West Roman Emperor again! That would give the popes an immediate ally, one who could confirm an election in weeks instead of months, and who would be more handy for instruction and correction, if necessary. A new West Roman Emperor. Somebody devout. Somebody militarily successful. Somebody, perhaps, from a dynasty (well, a polity) that had been Catholic unusually early, had already shown immense loyalty to the pontiffs, and already ruled half the West Roman Empire’s territory.

On Christmas Day, in the year 800, Pope Leo III (on rather dubious authority) crowned Charlemagne the restored Emperor of the West. The title would later be exchanged for the title of Holy Roman Emperor.

❧ FEALTY (fē-àł-tē). Sworn loyalty. From Latin fīdelitās, “faithfulness, trust.”

❧ FEUDALISM (fū-dàł-ĭz-ḿ). The Medieval political system defined by oaths of fealty. Interestingly, this term’s origin is not certain. It could be from the same root as fief, below; or from foderum, “fodder”; the present author wonders if it might derive from foederati, the status Romans granted to barbarian allies.

❧ FIEF (fēf).Territory (with agricultural income) held by a vassal from his lord. Possibly from (unattested) Old Frankish fehu, “cattle, livestock.”

❧ HOMAGE (hŏm-àj). Supreme fealty, first-priority fealty. From Old French hommage (of the same meaning). Not to be confused with homage (ō-mäzh) in the sense “artistic tribute.”

❧ LIEGE (lēzh). Paramount or supreme lord. From Middle High German ledic, “free, empty, vacant.”

❧ LORD (lõŕd). Leader or commander of men, especially one who receives oaths of fealty. From Anglo-Saxon hlæf-weard, “bread guarder.” Cf. hlæf-dige, “bread kneader,” which became modern English lady.

❧ SERVĪ (sêṛ-vē). Latin: slaves (sg. servus). At this time evolving, in sound and meaning, into serf.

❧ VASSAL (văs-àł). One who swears fealty to a lord, usually in exchange for a fief to subsist on. Possibly from (unattested) Gaulish wassos, “squire.”

1An emirate is the territory of an emir, an Arabic term generally translated “prince” or “commander.”

2“Clovis” is Latinized in form; his name in Frankish might have been something like *Hlōdowig (but little of the Frankish language has been preserved). A more common Latinization is Ludovicus; it may be from this, rather than the native form or Clovis, that Louis is derived. Other descendants include the English Lewis, the German Ludwig, the Italian Luigi, and a third Latin option, Aloysius. His descendants were called Merovingians after Clovis’ grandfather, Merovech or Marwig.

3The majordomo, often called in English the “mayor of the palace,” was the administrative head of the Merovingian government. By the early eighth century, the majordomo had become the true power of the realm, and the kings were figureheads.

4E.g., the first three Plantagenet kings of England (Henry II, Richard I, and John) were also Counts of Anjou, and in that respect theoretically subject to the kings of France—but only in matters pertaining to Anjou. As one can guess, this system became complicated quickly.

5Readers may be puzzled by the sloppy rhymes in this quote. However, chansons de gestes (“songs of deeds,” or Old French epics, like the Song of Roland) were not written to rhyme, but with assonance—i.e., the last vowel sound in each line was supposed to be the same, irrespective of consonants.

6A march is a borderland or “buffer zone,” in which there may be a mixture of laws and rights between the two adjacent realms; a noble who rules a march is a marquess (masculine) or marchioness (feminine) in English, though the French term marquis is sometimes used instead.

Gabriel Blanchard is CLT’s staff writer and editor at large, and a proud uncle to seven nephews. He lives in Baltimore, MD.

If you enjoyed this piece, you might be interested in our short intros to some of our Medieval authors and books, like St. Gregory the Great, St. Bede, The Thousand and One Nights, Hugh of St. Victor, the Nibelungenlied, the Pearl poet, and Lady Julian of Norwich.

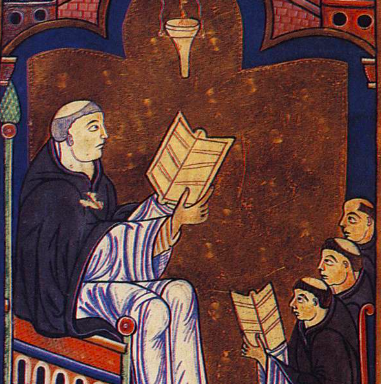

Published on 16th December, 2024. Page image of the Battle of Tours as depicted in the Grandes Chroniques de France, a High Medieval history of the French state and monarchy.