Texts in Context:

The Seven Crowns

of Engla-lond

By Gabriel Blanchard

If there is one thing we know about England during the age of the Heptarchy, it's that it isn't that, it's something else.

The Cassiterides

Last week, we saw the beginning of the Viking era in the sack of Lindisfarne that took place in 793. Lindisfarne was a little outside the Carolingian orbit (though we may expect the news affected Alcuin of York more than most of the Frankish court). As a sub-period of the Early Middle Ages, the Viking era lasted roughly two and a half centuries, if we consider the far-flung though short-lived North Sea Empire of Cnut the Great its limit.1

Of course, not everybody was restricting their calendars to “getting raided by Danes and/or Swedes (check local availability).” This was also a period of great importance to the perennial study of why Worcestershire2 is spelled like that: in other words, the English language. As English speakers, we may therefore take a geographically disproportionate interest in Britain.

The last few dozen centuries have proven a tad harsh on these islands. They lay under vast glaciers until the beginning of the Holocene (c. 9700 BC). In the Bronze Age, the British Isles received their first recorded bullying nickname: the Κασσιτερίδες [Kassiterides], i.e. “the Tin Islands” (tin, which is rare in most places but plentiful in the southwest of Britain, is one of the two key components of bronze). By the late first millennium BC, Celts of the Hallstatt and La Tène cultures had migrated there. A few hundred years later, the Romans invaded—first under the brilliant albeit dodgy Julius Cæsar; about a century later, his great-grandson3 Claudius succeeded in setting up a full-fledged Roman province of Britannia. Out of this province a few centuries later came a Romano-Briton named Constantine, and thereby hangs a tale, though one we’ll skip for time. Two months ago, we touched on the departure of the Romans from Britannia.

Sê Æwielm Lædenes Ûre4

By some lights, this is the point at which we should have begun to hint at the name of Arthur. Whatever his historicity, the context in which he is supposed to have been born and reigned was real enough: the fifth century saw the beginning of at least one wave of Germanic migrants from the mainland, principally Saxony, though some hailed from Jutland or Angeln.5

They brought their language with them, as one does. This was part of the group called West Germanic (which also produced Dutch, German, and Scots). By about the seventh century, these migrants’ tongue is referred to as Anglo-Saxon or Old English. They brought a script to write it in, too, a system of runes known as the futhorc. These runes dropped out of use after a couple of centuries, replaced by Roman script. However, futhorc influenced how the Roman alphabet would be used among Anglo-Saxons; for a time, futhorc even lent the Roman script letters for sounds not present in Latin, like þ (thorn), used for either pronunciation of th.6

In other respects, the Anglo-Saxon tongue was often surprisingly like Latin. It was inflected, with extensive systems of conjugation and declension; it also had a freer word order and grammatical gender. The grammar would be drastically altered in a few hundred years’ time, becoming Middle English by about the middle of the twelfth century, thanks to the influences of Anglo-Norman French and of Norse.

The Seven Crowns of Britain

From around the end of the sixth century until close to the middle of the ninth, “the England part” of Britain was politically divided into many petty kingdoms,7 known collectively as the Heptarchy. This name should not be taken literally: there were many more than seven realms, always coalescing and quarreling—Deira, East Anglia, Essex, Hwicce, Lindsey, Kent, Magonsæte, Surrey, and Wreocensæte8 still make an incomplete list. To the west and northwest lay Celtic realms like Cornwall, Gwynedd, Powys, and Strathclyde, the lattermost a predecessor of the Kingdom of Scotland. But only three or four of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms had real, permanent importance, and each had its own peculiar dialect of Old English. The realms in question were: Mercia, which lay in the heart of the island; Northumbria in the northeast; Wessex in the south; and, as an optional fourth, Kent in the southeast, probably thanks to its cultural importance as the home of the Archbishops of Canterbury. Over all of these principalities, not always in lawful power but in prestige, was the Bretwalda, the “high king” of the Britons. (At least, when there was a Bretwalda. And if that really is what the term meant.)

ᛁᚾ·ᚳᚪᛁᚾᛖᛋ·ᚳᚣᚾᚾᛖ·ᚦᚩᚾᛖ·ᚳᚹᛠᛚᛗ·ᚷᛖᚹᚱᚫᚳ···

ᚦᚪᚾᚩᚾ·ᚢᚾᛏᚣᛞᚱᚪᛋ·ᛠᛚᛚᛖ·ᚩᚾᚹᚩᚳᚩᚾ

ᛇᛏᛖᚾᚪᛋ·ᚪᚾᛞ·ᚣᛚᚠᛖ·ᚪᚾᛞ·ᚩᚱᚳᚾᛠᛋ

ᛋᚹᚣᛚᚳᛖ·ᚷᛁᚷᚪᚾᛏᚪᛋ·ᚦᚪ·ᚹᛁᚦ·ᚷᚩᛞᛖ·ᚹᚢᚾᚾᚩᚾ

ᛚᚪᛝᛖ·ᚦᚱᚪᚷᛖ···

[In Caines cynne thone cwealm gewraec ...

Thanon untydras ealle onwocon

eotenas and ylfe and orcneas

swylce gigantas tha with Gode wunnon

lange thrage ...]

On the kin of Cain, killings he wrought ...

Thence awoke all untimely births,

ettins9 and elves, and ogres also,

so too giants, such as strove with God

for a long season ...Beowulf, ll. 107, 111-114

Mercia was the largest and generally the most powerful of the “big three.” Curiously, its kings are never listed as having been Bretwaldas; this might be because Mercia was slower to be Christianized than the other realms. The rulers of Mercia were the only ones on the island who had already been a dynasty on the Continent. They spoke an Anglian dialect; the Gawain poet, who wrote in an archaic type of alliterative verse and came from the Midlands, may have been descended from Mercians and/or speakers of Mercian Old English, and J. R. R. Tolkien used their dialect to represent Rohirric in The Lord of the Rings.

Northumbria appears to have had something of a “melting pot” character. Its Christian practice reflected influences both from the Continent and from the Irish Church—small wonder, since this was the kingdom in which the Synod of Whitby was held, which formally regularized the relationship between the Celtic Church and the Roman. The arts of poetry and manuscript illumination both throve in Northumbria, and, besides Alcuin, it also nurtured the soul and mind of St. Bede the Venerable. The realm was more impacted by the Danelaw than the other two (more on that shortly), and its language, while basically Anglian like that of Mercia, was more influenced by Norse.

Finally, there is everyone’s favorite, the Kingdom of Wessex, or of the West Saxons, which was of course in the south of England. It was a comparatively small, poorly-documented realm in the seventh century, but showed a definite tendency to stay resilient against Mercian attempts to achieve top-dog status throughout the eighth. Its native dialect, called West Saxon, is fairly well-preserved, largely thanks to efforts of the late ninth-century King of Wessex and Bretwalda Alfred the Great. He relentlessly promoted improvements in education throughout his reign, and even translated some important works into Old English himself, such as Boethius‘ Consolation and St. Gregory‘s Pastoral Care. But one can hardly bring up Alfred the Great without mentioning …

The Bonus Fourth Realm

Even finally-er, we have the Danelaw. This was not mentioned among the Anglo-Saxon realms, because its people were not Anglo-Saxons but Danes, though the term “Norsemen” might be more apt here. The wave of Germanic people who wanted to settle in Britain was mentioned as a first wave; there were more; not all of the high prows sailing westward in that time were looking to pillage and go back home. And, naturally, the Danes did not speak Old English, but Norse—a language far more closely related to Old English than either was to Latin or Brittonic, but still a foreign one to Anglo-Saxon ears. (A sizable chunk of English vocabulary to this day is of Norse rather than Anglo-Saxon origins, including words like anger, awe, berserk, bleak, grovel, harsh, haunt, kidnap, ransack, regret, scathe, scowl, slaughter, thrall, thwart, ugly, weak, and of course ombudsman.)

Danes had been settling in Britain for years before this, but the Danelaw proper was established in the mid-ninth century. In the year 865, the Mycel Hæþen10 or “Great Heathen Army” landed on Britain’s eastern shore. The details of the ensuing war need not detain us right now—though it may be said that in this war, King Alfred earned, even if he never received, the name of being the first King of All England. In any case, and while the peace agreement did take the Hæþen out of the heathens—i.e., the Danes there agreed to become Christians—it also kept the ex-heathens in England. It would have been fruitless to try to drive them out: About the whole eastern side of England was part of the Danelaw, cutting the once-hegemonic Mercia in half.

The Bittersweet

Which brings us to our last book for this post. It is not known when Beowulf was written, or where, or by whom. Internal evidence dates it to the seventh, eighth, or ninth centuries. It is set primarily in the environs of Sweden, which could point to a poet who lived in the Danelaw; then again, Angeln and Jutland, the ancestral homes of the Angles and Jutes, are right next to Sweden too. Beowulf‘s material rather comfortably blends Christian and heathen ideas and images, which matches the seeming cosmopolitan aura of Northumbria—but it is composed principally in West Saxon, the least-Scandinavian-ized of the dialects in question.

Beowulf‘s final ending (not the slaying of Grendel—we’re talking about second final ending) has a “mixed melancholy” that seems characteristically English. For that matter, much the same could be said about the North Sea Empire briefly ruled by one who was, after all, a king of England first. A deed is achieved, but at a high price; neither element in the bittersweet wholly takes the other away.

1Cnut, or Canute, the Great (c. 990-1035) was King of Denmark, England, and Norway, a domain referred to by some modern historians as the North Sea Empire. He acceded to these realms at different times (in 1018, 1016, and 1028, respectively) and held them in personal union, not as a single polity. This only existed for about seven years, until Cnut’s death in 1035.

2For any who are unfamiliar, the English ceremonial county name “Worcestershire” is conventionally pronounced wüs-tŕ-shŕ; the person or persons responsible for this have never been caught.

3That is, Claudius was Julius Cæsar’s great-grandson legally, thanks to the adoption of Octavian (i.e. Augustus) and Octavian’s marriage to Livia (Claudius’ biological grandmother).

4Sē æwielm lædenes ūre is an Anglo-Saxon phrase meaning “the origin of our language.”

5Saxony then referred to most of the northwest of modern Germany. Jutland is the name of the Jutish Peninsula, i.e. the one Denmark’s on. Angeln, which probably gave its name to the Angles and thus to England, is a smaller peninsula closely adjacent to Jutland, on the east.

6The “ye” is phrases like “Ye Olde Book-Shop” was not originally a y, but a þ, eventually stylized beyond recognition.

7Petty kingdom is one of several set phrases (other examples include petty officer and petty cash) that use petty in an archaic sense, to mean “junior” or “small.”

8The name of Wreocensæte lives on to this day in the city of Wroxeter.

9Ettin is a Middle English cognate of the Norse jötunn, both conventionally translated “giant.” Both words seem to be distantly related to the word eat, and originally to have meant something like “glutton; devourer.” The term ettin appears in The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe in a catalogue of servants of the White Witch, and has since been resurrected in modern role-playing games.

10This is pronounced a little bit like “mew kill ha then.” The precise sounds of the y and the æ in Mycel Hæþen are those of the German ü and of the a in “cat.”

Gabriel Blanchard (who makes it a personal policy not to approach ettins, elves, or ogres, whether outside of or within the confines of ancient Wreocensæte) has a bachelor’s in Classics from the University of Maryland. He works as CLT’s editor at large, and lives in Baltimore, MD.

Thanks for reading the Journal and supporting CLT! If you enjoyed this piece, be sure to check out our podcast, Anchored—hosted by our CEO and founder, Jeremy Wayne Tate.

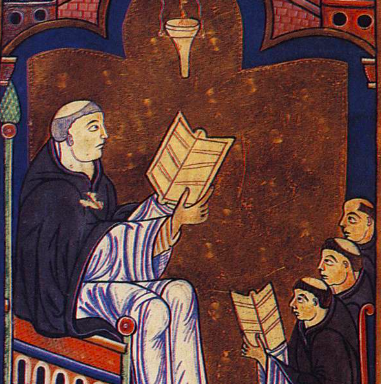

Published on 13th January, 2025. Page image of a map of the “Heptarchy” around the first half of the ninth century; this map was originally created for J. G. Bartholomew’s A Literary and Historical Atlas of Europe, published in 1914. This post received minor corrections on 15th January and 2nd October, 2025, receiving a few stylistic and display adjustments and some factual corrections: an earlier version of this post contained the false statement that the letter 3 (yogh) was also derived from the futhorc; we regret this error.

The quotation from Beowulf is given in futhorc. Other runic scripts were used outside Britain; some persisted as late as the nineteenth century. All runes descended from a script known as the Elder Futhark, which was devised roughly around the first century AD. The Elder Futhark itself was probably derived from an early Roman or Etruscan alphabet, derived in turn from the Greek script.

13th January happens to be the memorial of St. Hilary of Poitiers, a fourth-century bishop of that city and champion of Trinitarianism. A three-term calendar (as opposed to the two-semester calendar more usual in the US) is employed by Oxford University and Trinity College, Dublin; the second term always begins near this memorial, and is therefore known as the “Hilary term.” (This is preceded by the Michaelmas term—Michaelmas falls on 29th September—and followed by the Trinity term, a moveable feast which always falls in the summer.)