Trivialities and Quadrivialities

Is the Medieval-Classical Model of Education Truly Still Relevant?

By Gabriel Blanchard

The classical renewal movement has long argued that the skills of the Trivium are perennial. What, then, of the Quadrivium?

As we all know, the seven liberal arts are grammar, dialectic, rhetoric, mathematics, music, um, painting? and … virtue? No? Alright: grammar, dialectic, rhetoric, music, Sleepy, Sneezy, and Bashful? Red, orange, yellow, green …

The right list is as follows:

- Arithmetic

- Astronomy

- Geometry

- Grammar

- Logic (or Dialectic)

- Music

- Rhetoric

The seven liberal arts—so named because they were considered the proper study of free men, liberales in Latin—were the standard form of education that developed in the Greco-Roman world, and were codified as such by the time of Cicero. They were arranged into a set of three humanities, the Trivium, followed by a set of four sciences, the Quadrivium. The humanities were grammar (learning how to understand language down to its nuts and bolts), logic (learning how to use language to reason cogently from one idea to another), and rhetoric (learning how to use language beautifully and compellingly). In fact, the Trivium could be summarized as the study of human thought and communication; and since all teaching takes place by means of communication, there’s a strong argument to be made here that all education must include either the Trivium or something just like it.

Liberal though its subject matter might be, the Trivium was practical in its origins: it grew from the practice of law in cities like Athens. Civil suits could be brought at any time; crimes were as familiar then as now; and legal representation, far from being guaranteed, was virtually nonexistent. The norm was that the accused would defend himself, with all the skill in public speaking and long familiarity with the law that he … probably didn’t have, because most people at most times do not have those things (being too busy with “working for wages to spend on food,” and similar hobbies). A wealthy patron might help, for those lucky enough to have one; but the real solution was an education in public speaking—and since people were dealing with courts of law, not advertisements, the public speaking in question needed to be not just flashy but cogent, or at least offer a good pretense of cogency. The Sophists were not only embarrassed by Socrates’ exposure of their morally frivolous and destructive industry; he may have hurt their market too, since he caught them out in lies and showed that in at least one liberal art (dialectic), they were woefully deficient.

The disciplines of the Quadrivium, while they could be useful,* probably did not arise from an immediate societal need; it seems to have gained its aura of authority in a different way. Due to the association of both with mathematics, it may have borrowed the splendor of Pythagoras, who was not only famed as a brilliant mind but revered as a sage, even among Christians.

Unlike the theorem that bears his name, Pythagoras did not invent geometry or arithmetic, and astronomy and music were millennia old when he was born. What he did do was apply mathematics to every discipline, under the cryptic belief that “all is number.” The upshot was the discovery that the planets orbit at specific numerical intervals from one another, that musical chords relate to a the base tone of a scale through fractions, and much more; all, apparently, was indeed number! Centuries later, a Neoplatonist philosopher named Porphyry explained that all four subjects of the Quadrivium were mathematical. Arithmetic dealt with numbers in themselves; geometry, with magnitudes in themselves; music, with numbers in motion (the movement of a tune); and astronomy, with magnitudes in motion (the movement of the spheres).**

Charlemagne lived away back in the Dark Ages when people were not very bright. They have been getting bright and brighter ever since, until finally they are like they are now.

Will Cuppy, The Decline and Fall of Practically Everybody

But education changes, and the sciences changed with it. (Appropriately enough, it began with astronomy, less thanks to heliocentrism than to the implications of Tycho’s supernova.) Under the influence of empiricists and skeptics like Bacon, Hume, and Voltaire, the word science—which originally meant simply “knowledge,” from the Latin scientia—began to change. The importance of number or magnitude (in a word, quantity) remained the typifying trait of the sciences, but it was applied in a new way; now, the sciences studied all those things about which one could quantify results, in contrast with things that could not: there’s a scientific answer to how many pounds a granite pillar weighs, but not to how pretty it is. The Pythagorean premise that “all is number” had been quietly abandoned. Of the original four, only astronomy is still routinely called or thought of as a science today, and holds no special place in our schools.

The Trivium was not seriously challenged until the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Though it has by no means taken the field, it has regrouped admirably. The reign of the Quadrivium appears to be centuries dead; could it return? And if it could, should it?

First, besides not grieving “as others which have no hope,” we really need not grieve something that has, in fact, not died! The program of the Quadrivium has been dropped, and the material that composed it has been recontextualized; but that material is intact (and has indeed been vastly expanded). Students still study mathematics, and even use archaic books to do it. Astronomy may have lost its unique prestige, but the hard sciences in general certain command respect in our culture. In the same vein, music (now principally viewed from an artistic instead of a scientific standpoint) may not be a basic element of every curriculum, but it remains a common study and a popular hobby. Our previous organizing framework for all this knowledge has become little more than a curio; but the Quadrivium has not been ruined in the same sense that, say Lindisfarne was ruined by Vikings in 793. No dark age interrupted the transmission of knowledge; it was precisely advances in knowledge that made our old framework untenable.

Besides that, what made the Quadrivium important? It was not the disciplines in themselves—unlike the Trivium, in which it’s precisely the subjects that are important, inherently. According to ancient and medieval sources, the four disciplines of the Quadrivium amounted to something like “abstract and applied mathematics.” Insofar as we keep studying mathematics and (in the modern sense) the sciences, we are fulfilling the purpose it represents, whether our trappings are avant-garde or antiquarian.

*The universality of math is a commonplace, and geometry is vital for engineering anything bigger than a hut. Astronomy was useful as well: the reliable positions and cycles of the stars and planets made them a perfect tool for keeping time and navigating.

**Porphyry’s profile of astronomy may sound a bit like how we’d describe physics today. However, ancient-medieval astronomy and modern physics differ in their outlook on entropy: the ancients and medievals believed (based on the long-observed changelessness of the heavens) that everything beyond the Moon was made of a different kind of matter, æther, immune to decay. This meant that the physical laws governing most of the universe in the old model could not be properly understood, or sometimes even discovered.

__________________________________________________________________________________

Gabriel Blanchard is CLT’s editor at large. He lives in Baltimore.

The CLT has just seen a big win in the Florida legislature—in addition to other positive changes, our test now qualifies students for the state’s Bright Futures scholarship! Our founder, Jeremy Tate, was recently a guest on the New York Times’ First Person podcast, discussing the advance of the CLT and of traditional education in general. You can also find him and more CLT content on our own podcast, Anchored.

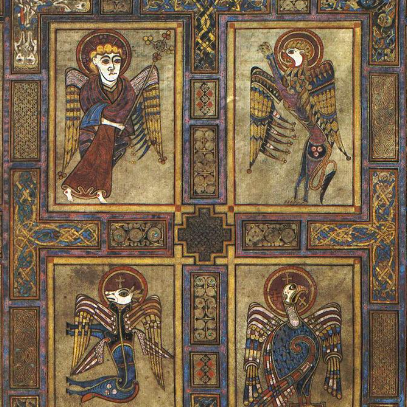

Published on 4th May, 2023. Page image taken from the painting St. Augustine in his Study (1480) by Sandro Botticelli. Author headshot replaced with a page from the Book of Kells, created in Scotland or Ireland ca. 800.