Von Goethe:

The Father of Romanticism

By Gabriel Blanchard

Goethe inaugurated a fundamental change in the passions that inspire literature in general.

Romanticism is an idea we tend to take for granted. I mean, romance, sure, big part of life; and John Keats and Samuel Taylor Coleridge certainly sound like names famous people would have, so if you say they’re great poets I’ll probably believe you.* But of course, that isn’t really what capital-R Romanticism means. It is more like variations on a set of themes than a collection of defined answers to a series of questions. These themes were a reaction against the professedly classical outlook of the eighteenth century, which the Romantics viewed as stifling the human spirit. They exalted autonomy over order, passion over law, imagination over logic, beauty over virtue, and in general, nature over human reason.

Romanticism is thus a kind of collective name for a large number of similar and interconnected, but independent and distinct, movements: the Decadents of late nineteenth-century France, the Pre-Raphaëlite Brotherhood of 1848, the Transcendentalists in America, the “Satanic school” of British expatriates Lord Byron and Percy Bysshe Shelley,† the one-man movement of the indomitable William Blake, the Sturm und Drang (literally “Storm and Stress”) movement in German literature—and this last brings us to today’s subject. Widely considered the single most influential author in the German language, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe was one of the first shapers of the Romantic movement (a little ironically, as we shall see). He was an eminent academic of his day, a statesman and scientist as well as a poet, dramatist, and prose author; he witnessed and in some ways exemplified the changes which were sweeping all across European civilization, particularly its changing relationship to Christianity.

One of Goethe’s first books was The Sorrows of Young Werther, an epistolary novel, i.e., one told in the form of a series of letters or other “in-universe” fragments. (Readers of Dracula or The Screwtape Letters will be familiar with the device.) Werther, the narrator and protagonist, writes to a friend about falling passionately in love with a young woman named Charlotte, but his love is hopeless, both because Charlotte does not return his feelings, and because she is in any case engaged to a man named Albert. Werther cultivates a friendship with both Charlotte and Albert, but is tormented by his affections, especially after their marriage. After an interlude away from the town, during which (thanks to being distracted by his passions) Werther humiliates himself by accidentally gate-crashing a party, he returns. Charlotte, out of sensitivity both to his feelings and to her husband, tells him he must not visit her any longer, and they bid each other a tearful farewell. Werther had hinted before that there could be no resolution of the situation while all three—Albert, Charlotte, and himself—lived; he writes to Albert requesting a pair of pistols for “a journey,” a request Charlotte sees through but nevertheless grants, and Werther uses them to commit suicide.

The novel was a roaring success, making Goethe a celebrity overnight. He actually distanced himself from Young Werther not long after its publication—thanks in part, maybe, to the string of copycat suicides it reputedly inspired—and even moved away from Romanticism in general, in favor of classicism! But the fame it acquired him guaranteed an audience for his later works, of which there were many, the most famous being a pair of plays: Faust and Faust: Part Two.

The story of a bargain with the devil is an old one, dating at least as far back as the sixth-century story of St. Theophilus of Adana, and arguably as old as the book of Job, as touched on below. The tale of Faust proper dates to the sixteenth century, and is based on a real person about whom rumors of this type circulated, and who was rapidly taken up by artists of the day as material. (The authoritative English version comes to us from Christopher Marlowe, the short-lived rival of Shakespeare; his play The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus was the first dramatization of the legend.) In the main, Goethe’s treatment sticks to the traditional plot. Faust is an honored and successful scholar, yet dissatisfied; the demon Mephistopheles appears to him and offers to make him practically omnipotent in exchange for his soul. Faust assents and enjoys a series of adventures, of which the climax is, or involves, conjuring the shade of Helen of Troy. At long last, the moment of death arrives, and—but here, tellings diverge. Many proceed to the obvious conclusion: the terms of the bargain fulfilled, Faust is duly taken to hell. Other tellings find a way of cheating the devil (as in Dorothy L. Sayers‘ play The Devil to Pay or the Disney film The Little Mermaid), whether by exploiting a detail in the contract or simply overpowering hell.

All intelligent thoughts have already been thought; what is necessary is only to try and think them again.

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Wilhelm Meister's Journeyman Years

Goethe modifies the tale in a few noteworthy ways. The first is the addition of a prologue set in heaven, in which a wager is made in advance over Faust’s soul between Mephistopheles and God. It resembles the challenges made by Satan in the opening chapters of Job, but with the added declaration on God’s part that he will surely have Faust’s soul in the end and is allowing Mephistopheles to tempt him only so that Faust will learn through the experience. Another is the addition of a young woman named Gretchen, whom Faust seduces; this in itself is standard enough, but in Goethe, she is a fully-rounded character, where hitherto only Faust himself usually received such treatment. Gretchen has a child by him, but drowns the newborn in a fit of madness, and is condemned to execution. Faust avails himself of Mephistopheles’ services to save her from the prison, but she refuses his offer; as Faust flees, a voice (implied to be from heaven) cries out, “She is saved!”

In its initial form, this is where the play ends—a satisfying theatrical conclusion to be sure, but structurally rather puzzling, in light of the promise in the prologue; Faust seems as yet to have learnt little, and his fate to all appearances is still up in the air. However, in 1832, twenty-four years after publishing the original and shortly before his death, Goethe completed Faust: Part Two, which brings the story forward to its finish.

Part Two has a more traditional five-act structure (its predecessor had multiple scenes, but no act breaks); most of its additions to the story are simply plot embellishments. Interestingly, most of Faust’s behavior remains pro-social even at its worst: rather than conjuring the shade of Helen to sate his carnal desires, he weds her; rather than playing obnoxious practical jokes on the authorities like Marlowe’s Faustus, Goethe’s Faust becomes a respected servant of the Emperor involved in land reclamation. But these very things hint at the sickness in Faust’s soul. When Helen, mourning the death of their son, forsakes the world once more, he does not pursue her but merely diverts himself with finance; in recovering land from the ocean, he is, literally, doing what is against nature; and when he spots two structures on his land that he does not own—a poor couple’s hut and a little chapel—he is enraged, and sends Mephistopheles to get rid of them. The demon proceeds to kill the inhabitants, driving Faust to realize that none of this is what he wants, and that he has wasted his life on what does not satisfy. He dies of shock, and Mephistopheles moves to collect his soul, but is distracted and obstructed by a group of angels, who carry Faust’s soul off to a wilderness populated by hermits. The Virgin Mary, referred to as Mater Gloriosa (“the Glorious Mother”), appears to Faust and the angels, in the company of three female saints, who all plead for the salvation of Faust. They are soon joined in doing so by a fourth spirit, soon revealed to be the soul of Gretchen. So far, so orthodox (by standards accepted literally by Catholics and for literary purposes by Protestants); but here we come to the final, and the strangest, change Goethe makes to his material.

The Virgin grants their request. The Mystical Choir about them then sings a hymn that concludes with the line, equally theologically puzzling to Protestants and Catholics, Das Ewig-Weibliche zieht uns hinan, “The Eternal Feminine draws us upwards.” Christian trappings have been blended with the conclusion of Apuleius’ ancient novel Metamorphoses, in which the goddess Isis—conceived of in her mysteries as not only the deity of the Nile but of all nature, and even as the supreme Godhead—delivers a devotee of hers from a curse‡; hence also, maybe, the phrase Mater Gloriosa (not an implausible title for the Virgin Mary, but also not a conventional one), and almost certainly the reason that she is addressed flatly as “goddess.” Of course it is improbable that Goethe was arguing, in the style of a popular cartoonist, that the Virgin Mary was secretly Isis! But he may have been advancing a pantheistic or syncretic view that both represented the same divine impulse or aspect of the spirit, ruling, or ruled by, or one with, the unsullied goodness of nature. His renunciation of Romanticism, it would seem, was not total after all.

*How we got away with naming a poet William Wordsworth, on the other hand, I really don’t know.

†These poets likely gained the unwholesome moniker “the Satanic school” for several reasons. Their beliefs were unorthodox to the British public (Shelley was an atheist, and Byron’s desire to have his third daughter raised a Catholic was hardly less scandalous at the time); their morals were openly irregular, flouting their own marriages and other people’s; and their political sympathies were revolutionary, which they expressed in part by interpreting Satan as not just the protagonist but the hero of Paradise Lost.

‡Apuleius’ Metamorphoses should not be confused with the work of the same name by Ovid! Apuleius was several generations younger, living in the mid-second century, and was an initiate of the mysteries of Isis. The mystery religions were groups whose followers were forbidden to reveal the secrets of the deity into which they had been inducted, and which generally promised them eternal life. The Eleusinian mysteries are the most famous, and those of Isis and Mithras (derived from Egypt and Persia respectively) were also popular. Primitive Christianity has occasionally been interpreted as a mystery religion, or as drawing upon them.

__________________________________________________________________________________

Gabriel Blanchard is a proud uncle of seven nephews, a freelance author, and CLT’s editor at large. He lives in Baltimore, MD.

If you’d like to read more from the Journal, take a look at these essays on faith and technology, or these profiles of St. Hildegard and Albert Camus. Looking for audio or visual content? Check out our YouTube page, or our podcast, Anchored.

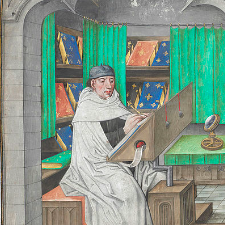

Published on 26th June, 2023. Page image of Twardowski and the Devil by Michal Elwiro Andriolli (1895); the Polish legend of Twardowski closely parallels the story of Faust, though whether either tale influenced the other is unclear.