Texts in Context:

Varangians and Vinlanders

By Gabriel Blanchard

In the tenth century, northern Europe (with exceptions and false starts) is seen at last to enter the circle of post-Classical civilization.

Easterby and Westerby

As we began to cover last week, Erik the Red’s colonization of Greenland—though not without hardship, including enormous loss of life on the initial party’s journey west—was essentially successful. Our primary sources for this history are Grœlendinga Saga, or “The Greenlanders’ Tale,” and Eiriks Saga Rauða, or “The Tale of Erik the Red.” Both are imperfect and occasionally contradict each other; they postdate the events they record by a couple of centuries, and are in all likelihood embroidered in places, but the essential outlines of their story are thought to hold.

In 985, the Eastern Settlement (Eystribygð, which we might name “Easterby” in English1) was established in the fjords by Cape Farewell, the southern tip of Greenland. It lay in about the same place as the modern town of Qaqortoq, and would remain by far the largest Norse colony on the island. Shortly thereafter a much smaller settlement was founded, roughly at Nuuk, modern Greenland’s capital; since it was located a little over three hundred miles to the north, it was naturally called the Western Settlement (Vestribygð, or “Westerby”).

Life in Norse Greenland was tough, but manageable, thanks to both the Medieval Warm Period and the Gulf Stream. The latter carries seawater from the Gulf of Mexico all the way to Greenland, Iceland, and the British Isles, tempering what would otherwise be far more brutal climes. Subsistence farming was possible in the deep fjord valleys, away from icy polar winds that prevail over the Labrador Sea. Indeed, conditions were unusually good in some respects: infant and child mortality rates seem to have been lower than average, and diseases were relatively few. Moreover, Greenland was rich in trade goods: besides resources they were able to raise themselves (such as wool), seal and polar bear furs, gyrfalcons,2 narwhal3 tusks (sold as “unicorn horns”), and especially walrus ivory. Ivory (whether polar or tropical) was extremely valuable, ranking with gemstones and precious metals at the time; it was frequently used to carve sacred objects like croziers and reliquaries, and also for pieces in a war game that had recently been imported from the partly-Arabized culture of Spain, called “chess.”

Nordic Crosses

Erik the Red was an avowed, lifelong pagan; however, this was becoming unusual among the Norse. Despite the Viking habit of sacking monasteries and cathedrals, there seems to have been little persecution of Christianity in Scandinavia, or in most Scandinavian colonies (with the eye-catching exception of the Danelaw, where the Mycel Hæþen4 martyred King Edmund of East Anglia in 869). Erik’s eldest son Leif departed Greenland some time around 995, to spend time in the service of King Olaf I of Norway; he got back around the year 1000 (after a detour, which we will come back to) with a Christian priest in tow, by Olaf’s request.5 Leif Eriksson was credited with converting most of Greenland, including his mother; his father seems to have been less angry than annoyed at the idea.

It is a little funny Greenland was Christianized just when it was: Three thousand miles to the east, the Varangian princedom of the Kyivan Rus’ was also in the midst of a society-wide conversion. Christianity was apparently much ridiculed for a long time by the Rus’6—perhaps for its precepts against violence and retaliation. Still, here as in Norway or Greenland, little to no material persecution seems to have been the norm, and conversions did happen, even from the royal household.

St. Olga of Kyiv is a good (and topical!) example. She had been the consort7 of Grand Prince Igor, son of Rurik I; widowed in 945, she then became dowager8 Grand Princess regent on behalf of their son, Svyatoslav I. In this capacity, she traveled to Constantinople in or around 955, and there became a Christian. St. Olga was unable to persuade her warlike son to convert: Her three grandsons, Yaropolk, Oleg, and Volodymyr, grew up in the local Slavic form of paganism. Whether she perhaps wielded some influence on Volodymyr nonetheless is hard to say, but the question arises fairly naturally; for it would be Volodymyr (or Vladimir) who effected the conversion of the Rus’.

It was not at first obvious that this would happen. For one thing, it was by no means clear that Volodymyr would ever be the Grand Prince of Kyiv; he was not only the youngest, but illegitimate, holding a title of nobility but decidedly beneath his elder brothers. However, in 977 (five years after Svyatoslav’s death), and despite Slavic paganism and Christianity agreeing that you mustn’t kill your brothers even a little bit, Yaropolk Cained an Abel of the middle brother, Oleg. Volodymyr fled the country, returned with an army, and ultimately did the same to Yaropolk—who did start it, to be fair. Even so, fratricide is not typically on the list of saintly qualities; and between his eight hundred concubines and his inaction when two Christians were abruptly lynched by the Rus’ populace, Volodymyr did not give the impression of being eager for baptism in the first place. Even when he did convert in 988, it was avowedly for the hand of the Emperor’s sister in marriage.

Those corsairs, whom we have so often seen plundering Christian countries, sought baptism, sometimes on the very site of their rapine; and their change of heart even led them to steal relics—a sure proof, in that age, of their great faith.

H. Daniel-Rops, The Church in the Dark Ages, Chapter X: The Tragic Dawn of the Year 1000

That said, whatever his motives, Volodymyr does seem to have meant it. Perhaps he was simply the sort that always keeps a vow no matter why he made it—which is rather the point of a vow, after all. On returning to Kyiv with his new bride, he did summon all his subjects to be baptized or risk the enmity of their prince, which was to be expected. But he also destroyed (both by policy and personally) a large number of idols, including some he had put up himself several years before. Some parts of the Kyivan Rus’ remained hostile to the new faith, especially the more remote provinces of the north, but, like their prince, the Rus’ nobility did not stint to threaten reluctant converts. (To reiterate a line we recently took up from Charles Williams, “Those conversions prepared the way for the Church of the Middle Ages, but the forcibleness of the conversions also prepared the way for the Church of all the after ages.”)

Vinland: A Premonition

But returning to Leif Eriksson’s detour. He did come back to Greenland, but not before a chance wind blew him over six hundred miles further west than he had intended to go. He there chanced upon some land, explored it a little, gave it the name “Vinland,” … and left. There was a small, short-lived effort at setting up a village there later on (probably at L’Anse aux Meadows, a site at the northern tip of what we now call Newfoundland); Leif was not a part of that expedition. The Norse attempt to colonize Vinland fizzled out rapidly—unlike their claim on Greenland, which would hang on until at least the early fifteenth century.

This transitory-ness may, perhaps, be why Leif has had a hard time holding onto the credit for his accomplishment. Even today, Columbus is said by some people to have “discovered” the New World, ignoring not just Leif but all the people who had already discovered it so confidently they outright lived here. But, whatever worth we assign to the question, the first European to cross the Atlantic was not Christopher Columbus: It was Leif Eriksson. Moreover, he gave the land he found a good name—one that was neither objectively wrong (like Columbus, who went to his grave convinced he had reached the Orient), nor arbitrarily derived from a European (like Amerigo Vespucci). He quite sensibly named it for something he found there, namely grapes—Vinland, “the land of wine” or “of the vine.”

Why Vinland proved to be a false start when Greenland throve is difficult to say. The odds were stacked against Vinland, though: It was even more remote than Greenland, and Greenland, which was not exactly bursting with excess people, was the only real staging area for a Vinlander colony. Moreover, there were people living there already. Now, this was true in Greenland as well, which was part of the regions settled by the Inuit. (The Norse called the local peoples of both Greenland and Vinland skrælingar or “Skrælings,” a word of unclear but likely unflattering meaning.) However, the Inuit and the Norse didn’t compete for resources as much as one might think. The former were mainly arctic hunters, where the latter were subartctic farmers; on the whole, Norseman and Inuit stayed out of each other’s way, simply out of convenience. But the locals in Vinland did seem to be interested in the same resources as the Norse, and, despite one or two initial friendly interactions, relations rapidly soured. All in all, it was too much effort for a settlement they didn’t need: Vinland was forgotten.

Still, it is intriguing to wonder what the world would be like otherwise. What if the Early Middle Ages, rather than the Renaissance, had been the time when contact was established?—a period when something far closer to technological equality, at least, prevailed between the peoples on either side of the North Atlantic.

1The element easter– here is an archaic alternative to “eastern”; the same relation holds between wester– and “western.” The suffix –by is what the Norse byggva (“to build, put up”) or its derived noun bygð might have become in English, a bit like the sound of the (unrelated) town name “Tenby” in Wales.

2Gyrfalcons are a tundral species native to Eurasia and North America, including Iceland and Greenland, which were popular for falconry. Other birds were and are also used, such as the peregrine falcon and the Levant sparrowhawk.

3The narwhal, which has the delightful scientific name Monodon monoceros, is a type of toothed whale (related to beluga whales, porpoises, and dolphins) native to the Arctic Ocean. Adult narwhals range from a little under ten feet in length to eighteen feet; males (and occasionally females) possess a hollow, spiraled tusk, which can range approximately between five and ten feet.

4A.k.a. “the Great Heathen [Army],” principal foes of King Alfred the Great.

5This is not Saint Olaf, the national patron of Norway; he was the king after next.

6Rus’ (singular and plural) is the usual name of the ethnicity as well as of the state, though Russes is occasionally used for the former.

7A consort—usually an empress, queen, prince, or princess—is the spouse of a reigning monarch, who holds a title only by virtue of their spouse’s office. A spouse who holds their noble title in their own right is regnant rather than a consort. For instance, from 1688, Queen Mary II was recognized as a queen regnant. Her husband, William of Orange, would normally have been her prince consort (consorts cannot hold titles which “outrank” their spouses, and kings traditionally outrank queens in Europe; so regnant queens’ consorts get “the next title down”). However, Her Majesty took the throne on the condition Parliament make her husband King of England, a regnant monarch rather than a consort; this is why he received a regnal number as King William III, and also why he continued to rule after Mary’s death in 1694.

8In the strictest usage, dowager means any woman living off of a dower (a legacy, usually in land, that a man settled on his wife to support her after his death—not to be confused with a dowry, which came from the bride’s family at the beginning of the marriage!). In practice, it is used only for empresses, queens, and princesses consort, as in expressions like “the queen dowager.” (Note that both consort and dowager fall into the “Norman” set of English political terms which place adjectives after nouns, as in French; the famous example is “attorney general.”)

Gabriel Blanchard has lived in Vinland for over thirty-four years, because he isn’t a quitter; more specifically, he lives in Baltimore, MD. He works for CLT as the company’s editor at large.

If you enjoyed this piece, check out our “Great Conversation” series on the history of ideas. It covers concepts as wide-ranging and intricate as authority and language, and also some more surprising entries in the list, like games, infinity, and magic. And don’t miss our podcast, Anchored. Thanks for reading.

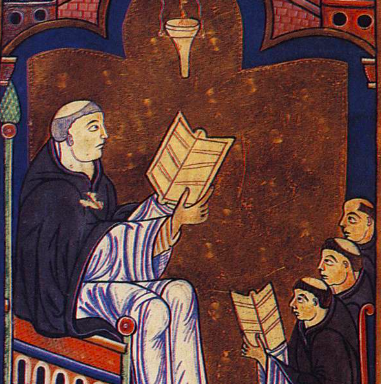

Published on 28th January, 2025. Page image of a leaf from the Arkhangelsk Gospel, a lectionary composed in 1092 in Old Church Slavonic (a language which holds a similar status in Eastern Europe to that of Latin in Western); this is one of the oldest Russian liturgical books still in existence.