Dante

An Author Profile

First Canto: Morte

By Gabriel Blanchard

The canon of literature is like a lofty tower composed by hands that seem superhuman, for there were giants in the earth in those days. Yet one poet surpassed storied Babel; for he did reach unto heaven, and make a name.

❧ Full name and titles: Dante (or Durante*) di Alighiero degli Alighieri [dän-tā or dû-rän-tā dē ä-lē-gyā-rō dĕł-yē ä-lē-gyā-rē; see our pronunciation guide for details]

❧ Dates: May (?) 1265-14 Sept. 1321

❧ Areas active: Republic of Florence; the Papal States; several city-states of northern Italy (Verona, Sarzana, Lucca, Ravenna); the Republic of Venice**

❧ Original languages of writing: Latin, Medieval Italian (Florentine dialect)

❧ Exemplary or important works: The New Life (often known by its Italian title, La Vita Nuova); The Divine Comedy; Monarchy (De Monarchia); Vernacular Eloquence (De Vulgari Eloquentia)

The world-wide, centuries-long fame of Dante somewhat belies the quality of his life. A patriot, he spent the greater part of his adult life in exile from his native city; a public-spirited idealist, he saw the hero who embodied his civic ideals die ignominiously and with no legacy. A passionate romantic, Dante never had the opportunity to marry the woman he loved, who died at only twenty-four years of age. A devout Catholic, intensely loyal to the Church, he lived through an era of priestly and monastic corruption that was only becoming more loathsome, decade by decade and papacy by papacy (indeed, one of Dante’s most famous personal enemies is also widely held to be one of the worst popes ever to reign). But we are getting ahead of ourselves; we must set our charge on the way of life, before he can be lured into this dark and pathless forest.

Dante was born in or around 1265, in Florence. His family, the Alighieri, claimed descent from the people of Rome itself; they were not opulently wealthy, but they were comfortable. We know little else about Dante, until he was about nine years of age; the following episodes come from his book La Vita Nuova or “The New Life,” in which he recounts experiencing romantic love as a means of divine grace—almost as a sacrament.

One morning, while visiting with his father in someone else’s house, he encountered a girl, about a year younger than himself. Her name was Beatrice. By his own account, he was thunderstruck, though it is not even clear whether they spoke. Every level of his being, he explained, was affected—what we might call the head, heart, and gut. His gut lamented what it knew would be a pain to deal with (love, especially when conducted according to the conventions of courtly love, is not known for being a comfortable experience). But his mind told him Here is a god stronger than I, who cometh to rule me; and his heart said, Now is thy bliss made manifest.

The experience was repeated and magnified nine years later, when he was eighteen. Walking about in Florence, he passed by Beatrice; and this time, we do know that they exchanged words, or at any rate that she said something to him: Salute.† As lovers will when the near-stranger they have worshiped from afar says “Hello,” Dante more or less came to pieces at this gesture; he said he felt so overwhelmed by grace in that moment that he forgave everyone for any wrong they had ever done him, and that if anyone had asked him a question, he would only have been able to reply, “Love.”

The bliss of these first two encounters did not last. Before long, she had heard a nasty rumor about him, and thereafter snubbed him—or as he put it, “denied me the bliss of her salute.” In the year 1290, Beatrice died, and the whole city seemed bereaved to Dante. Ultimately, he resolved to lay his work on Beatrice aside, at least for the present, and pour his energies into public affairs.

Florence was then subject to the Holy Roman Empire. The Emperors had a centuries-long rivalry with the Popes, and the Papal States occupied most of central Italy, bordering imperial territory. Unsurprisingly, their quarrel was reflected in a rivalry between two political factions: the Guelfs, who supported constitutional government, and the Ghibellines, who favored a more aristocratic regime; in theory, of course, the members of both parties were all Catholics and imperial subjects, but practically speaking, the Guelfs were backed by the Pope and the Ghibellines by the Emperor. Florence was solidly Guelf in Dante’s time—but then the Guelfs of Florence underwent a nasty internal split. The White Guelfs were moderates, wanting limits on the Pope’s direct political clout; the Black Guelfs continued to give the Popes their full support, political as well as religious. It was the Whites who controlled Florence at the turn of the fourteenth century.

By 1301, Dante was a successful man, albeit a little hampered by his reputation for being aloof and haughty. A veteran and a White Guelf, he had had a minor but respectable political career, and made a name for himself as a poet; in fact, he had helped found a new school of poetry, the dolce stil novo or “sweet new style.” This movement not only daringly blended courtly love with Catholic orthodoxy—something scarcely even attempted by earlier poets of courtly love, who tended to be on the Lancelot side of things—but did so in the vernacular (which Dante especially promoted). However, this year would prove fateful.

Io non morii, e non rimasi vivo ...

I did not die, and did not stay alive ...Inferno XXXIV.25

The pontiff at this time was the notorious Boniface VIII, and his outlook on the papacy was, ah, not aligned with that of the Whites. A near-contemporary Florentine historian named Giovanni Villani described the pontiff thus:

He was very learned in the Scriptures, and of great natural parts, and a very prudent and able man … very haughty and proud and cruel to his foes … and greatly feared by all, and he greatly exalted and magnified the state and counsels of Holy Church. … He was magnanimous and generous to those who pleased him … very avid of worldly pomps according to his degree, and very covetous, not looking closely nor keeping a strict conscience when it was a question of gain … He was more worldly than befitted his dignity, and he did many things which were displeasing to God.‡

And in 1301, as northern Italy lay mired in internecine quarrels, Pope Boniface VIII turned his attention to Florence: he called for Charles of Valois, the brother of the king of France, to enter northern Italy as a mediator. The Florentines sent a delegation to Rome to divert or delay it, Dante being one of its members; the Pope sent most of them back, but requested that Dante remain. While he was residing in Rome, the Black Guelfs were running amok. The property of important Whites was mostly seized, and several members, again including Dante, were exiled from the city.

Boniface VIII certainly “got his”: only a year afterward, in retaliation for the issuing of the bull Unam Sanctam, which made the boldest claims for papal authority in history, the Pope was kidnapped by soldiers of the French king. The French treated His Holiness so roughly that, though freed from them after only a few days, he died of shock a matter of weeks later. Those who have been told the old, lazy lie that Dante “put all his friends in heaven and all his enemies in hell” (a lie which can be exploded by the simple expedient of actually reading the Comedy) may be surprised to learn what the poet said about these things being perpetrated against a man whom he considered hateful to God, a simoniac, a hypocrite—but for all that, a Pope: “Christ led captive and crucified in the person of his Vicar.”

Dante’s hopes did not fail for a while yet. He became a peregrine scholar, staying with noble benefactors in Lombardy; he continued writing. And then, in 1309, an all but miracle occurred. The Holy Roman Empire had been in interregnum for over sixty years, yet now, at last, a new Emperor had been chosen. Dante’s political theory was strongly monarchist. He considered unity under imperial rule not only divinely ordained, but the sole hope for civic justice and peace, since, absent a centralized authority with final say over all temporal disputes, those disputes could simply carry on forever, and ruling the world was not part of the Pope’s job description. The new Emperor, Henry of Luxembourg, viewed his own office much as Dante did, and restored the poet’s hopes for a united Italy as part of a reunited Empire—and with it, at long last, his own return home to Florence. Henry came in person to Italy, both to be formally crowned in Rome and to restore the allegiance and peace of the northern Italian cities, each of which had far-flung populations of political exiles. It was on this occasion that Dante composed his political tract Monarchia, which argued for the independence of the secular and ecclesiastical powers from each other and that they ought not, and in fact could not, usurp one another’s functions.

But soon everything was going wrong. Henry VII had hoped to win both sides over merely by courteous justice. Alas, his insistence on amnesty for all political exiles, Ghibelline and Guelf alike—after all, they were both his subjects, were they not?—rankled the Guelfs especially, and he needed to put down several revolts; Florence shut her gates to him and prepared for war. Worse, though the Emperor traveled to Rome in 1312, as he had said he would, it transpired that Boniface’s successor Clement V would not be keeping his prior commitment to crown Henry there. And then, while besieging the rebellious city of Siena late that August, he contracted and promptly died of malaria. He had reigned over the Holy Roman Empire for just over four years.

It was over. Dante had lost his love, his innocence, his ambition, his home, and his dream. What else was there?

Go here for the second canto.

*The name Durante, of which Dante is a shortened form, does not appear in surviving papers from Dante’s own lifetime, but a document belonging to his son Jacopo refers to him as “Durante, often called Dante.” The long form was also the name of his grandfather, for whom he was likely named.

**Limited evidence suggests that he may have traveled to Paris at some point, and even Oxford, but most scholars dismiss this.

†In Medieval Italian, salute (pronounced sä-lû-tā) could mean “salvation” or “health” (meanings not typically distinguished in Latin, or Greek), but it was also a common greeting.

‡This version appears in Dorothy Sayers’ introduction to her translation of the Inferno.

__________________________________________________________________________________

Gabriel Blanchard has a bachelor’s in Classics from the University of Maryland, College Park. He lives in Baltimore, MD, and works as CLT’s editor at large.

If you enjoyed this piece, you might also like some of our other material on the men and women of our Author Bank, from classical antiquity down to the modern day: we have posts on Livy, St. Gregory of Nyssa, St. Benedict, the Brothers Grimm, Albert Camus, and many more. If you’d like a more topical look at the history of thought, check out our series on what the late Mortimer Adler referred to as “the Great Conversation.” Thank you for reading the Journal.

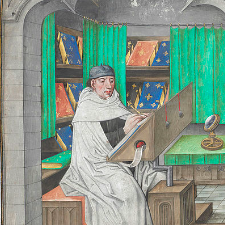

Published on 4th December, 2023. Page image of Dante and Beatrice (1883) by Henry Holiday, a Victorian painter influenced by the Pre-Raphaelites. The woman in gold is Beatrice.