Sojourner Truth

An Author Profile

By Gabriel Blanchard

The tall, lean shape of Sojourner Truth strode tirelessly across the North, carrying the law and the gospel of freedom in its mouth.

❧ Full name: Sojourner Truth [sō-jøŕ-nŕ trûth], formerly Isabella Baumfree [ĭz-à-bĕl-à or ĭz-à-bĕl-à bōm-frē; see our pronunciation guide for details]

❧ Dates: c. 1797-1883

❧ Areas active: the United States (mainly New York, New England, Ohio, and Michigan)

❧ Original language of writing: English

❧ Exemplary or important works: Narrative of Sojourner Truth: A Northern Slave

The eighteenth and nineteenth centuries in North America fostered a long dynasty of enslaved men and women who not only found a way out of slavery, but determined to help make a path for others. Among them were Harriet Tubman (who earned the nickname “Moses” for her exploits), Frederick Douglass, and Toussaint L’Ouverture (leader of the Haitian Revolution); today, we look at Isabella Baumfree. This surprisingly imposing figure—reputedly six feet tall and with a deep, booming voice—is better known by the name she took in 1843, Sojourner Truth. One of the striking traits of her story is the simple detail of where she was from: New York. New York fought for the Union in the Civil War, so we habitually think of it as a free state; and this is quite true—after 1799.

All of the Thirteen Colonies legally permitted some form of slavery at first.* Slavery was not always clearly distinguished from indentured servitude. This institution had a maximum term of service (typically seven years), but the term could be extended as a legal punishment for offenses like running away or damaging their master’s property. The first recorded sentence to explicitly lifelong servitude in the colonies took place in Virginia in 1640; three such servants—two white men, and a black one named John Punch—were captured after an attempt to run away. The two each had another year added to their indenture, but Punch was condemned to remain in servitude for the rest of his life. The very next year, Massachusetts legally recognized slavery, and the legal status of the black population (even, sometimes, the free population) in the colonies continued to decline from there.

About a generation after the Punch case, commanding support both from whites and free people of color, Abolitionist movements sprang up in the North and the South alike in the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, driven largely by Baptist, Methodist, and Quaker preachers; a wave of manumissions also followed the American Revolution (either given in person or included as a clause in the master’s), often citing its philosophic and political underpinnings as their inspiration.

And how came Jesus into the world? Through God who created him and the woman who bore him. Man, where was your part?

Sojourner Truth, "Ain't I a Woman?" (Robinson recension**)

These were local, individual changes, but Abolitionism was seeing successes too: in 1780, Pennsylvania became the first state to outlaw slavery, with others on its heels. Slavery was not, as a rule, abolished immediately; gradual elimination was more practical, for slave-owners. Often, those born into slavery up until a given date were “grandfathered out” of the emancipation, as it were. Isabella Baumfree was one of New York’s unlucky ones, born in 1797 or thereabouts, and slavery was not set to be completely abolish in New York until 1827. Multiple masters abused her; one, John Dumont, conceived at least one child with her by rape—which, very unfairly and very predictably, drew Mrs. Dumont’s wrath against Baumfree rather than her husband. Dumont promised to manumit Baumfree a year early, but then went back on his word. Eventually, fittingly enough in 1826, the year the broken promise would have been kept, she decided to escape.

She was forced to leave three of her four living children behind (her first child had died in infancy); only her infant daughter Sophia was with her. After her departure, her son Peter was illegally sold to a master in Alabama, right at the other end of the country as it then was. Nevertheless, two relentless years later, Isabella Baumfree became one of the first black women in US history to go to court against a white man and win. For about twenty years, Peter was restored to her. Tragically, he disappeared a second time in 1842: having taken a job on a whaling ship (during which mother and son noticed at least two of his letters went astray, and all of hers), when it returned to port, he was not there.

One might have expected, after a life that had already been so cruelly demanding, that this would be the straw to break the back. If anything broke, that thing was not Isabella Baumfree. The next year, sensing what she believed to be a divine calling (and it was on the day of Pentecost that year), she both changed her name to Sojourner Truth and adopted the vocation it suggested. All she took with her were a handful of personal possessions in a single sack, and she began to travel up and down the northeast, promoting the causes of abolition, securing the voting and property rights of Black Americans, and women’s suffrage. It was in this period that she delivered the speech commonly cited and quoted under the title “Ain’t I a Woman?”** When the Civil War came, she lent her rhetorical talents to the Union cause, appealing for recruitment; in 1864, she was a guest of President Lincoln at the White House. Truth forged friendships with a number of other prominent abolitionist, anti-racist, and feminist activists of her time as well, including William Lloyd Garrison, Susan B. Anthony, Fredrick Douglass, Lucretia Mott, and Harriet Beecher Stowe.

In her final illness, Truth was cared for by two of her daughters; she died in 1883. Her tombstone bears the inscription Is God dead?; “and thereby hangs a tale.” Reputedly, Frederick Douglass—who certainly was a seasoned rhetorician with a gift for answering hecklers—delivered a speech in Boston in a state of despondency; he foresaw no ultimate success for the cause of abolition among the white majority, and predicted in consequence a disastrous slave revolt which would not effect its aim either, but only produce immense bloodshed. Suddenly, the gaunt, six-foot-tall figure of Sojourner Truth rose, and boomed at him: “Frederick, is God dead?”

*The sole exception to this, at first, was Georgia. James Oglethorpe, the founder of the colony (and one of the British leaders in the hilariously-named War of Jenkins’ Ear), convinced Parliament on economic and moral grounds to outlaw the practice from the colony’s founding in 1732; however, this decision was reversed in 1750.

**There are a difficulties about the text of this speech, which was given at the 1851 Women’s Convention in Akron, OH. It is known in two principal forms: one is a transcription made by the Rev. Marcus Robinson, the secretary of the convention, who worked with Sojourner Truth. He published this version in the Anti-Slavery Bugle, about a month after the speech was given. This version does not contain the repeated rhetorical question “Ain’t I a woman?” that characterizes the other recension. This, by far the more famous, was related by Frances Dana Barker Gage, who presided at the convention. It was long accepted as the authoritative text, but it contains several problems, highlighted by historian Nell Irvin Painter. The two most important are that it was not published until 1863, twelve years after the fact, and that it is heavily dialectal—not in itself improbable, but the dialect is that of mid-nineteenth-century Southern slaves, not of Northerners like Truth. (Truth’s own native language was New York Dutch, a survival from Dutch colonization of the region; Truth reportedly took pride in her excellent English, and a native New York Dutch speaker would have been able to master English with very modest efforts.) Accordingly, though still known under the title derived from the Gage version, Robinson’s text is almost universally considered the more reliable.

Gabriel Blanchard is CLT’s editor at large. He holds a bachelor’s in Classics from the University of Maryland, and is a proud uncle to seven nephews. He lives in Baltimore, MD.

If you enjoyed this piece, be sure to tune in to our podcast, Anchored, hosted by CLT’s founder, Jeremy Tate. Thank you for reading the Journal.

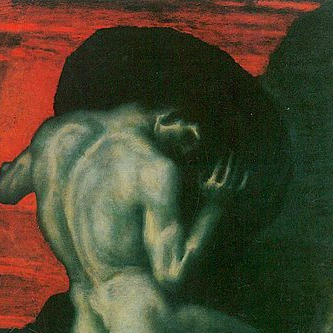

Published on 23rd October, 2023. Page image of Josiah Wedgewood’s celebrated abolitionist image, depicting a manacled African and bearing the inscription: “Am I not a man and a brother?”