Texts in Context:

From Antiquity

to the Mediævum

By Gabriel Blanchard

We have come now to, perhaps, the most libeled and distorted period in all of human history. Let's clear a few things up before we properly begin!

“The Dark Ages” Are Not a Thing

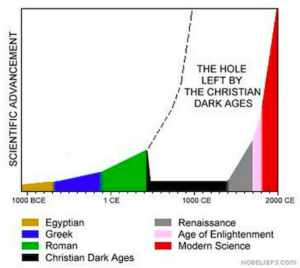

Many people already know of what is often called simply THE CHART. For those not familiar with THE CHART, here it is, in all its ludicrous glory:

Few people would propose something so simple-minded today (if only due to THE CHART‘s precedent). However, it is still widely believed that the Middle Ages—the whole ten-century period, roughly from 500 to 15001—were a time of unrelieved superstition, filth, and ignorance, imposed on the populace by a nigh-omnipotent, aggressively backwards Catholic Church, and any push from modern historians to stop calling them “the Dark Ages” is just chronological wokeness or something.

This could scarcely be further from the truth. Many of the most important developments in Western history began during this period, no matter what discipline you choose to examine. The scientific method is arguably the fruit of the Middle Ages. They were certainly where we got the idea that romantic love is a valuable, positive thing.2 Many crucial discoveries and inventions date to this era, including Arabic numerals, the compass, eyeglasses, gunpowder, the hand grenade (really!), the printing press, the stirrup, and the windmill. The game of chess, moving west from India,3 took its modern form in Europe in the Middle Ages. The groundwork for all modern economic theory was laid by the invention of double-entry bookkeeping in thirteenth-century Florence and the debates over the Franciscan ideal of absolute poverty about the same time. The Mediævum4 is when Europeans discovered the Americas, twice. And we’ve said nothing yet of the artistic, philosophical, legal, or architectural accomplishments of the period, from the Summa Theologica to the Divina Commedia.

This is not to say the Middle Ages had no problems. Every period does. Some popular myths even contain kernels of truth: for instance, it was normal to use torture in examining witnesses during trials. It’s also true that our Medieval ancestors simply didn’t know certain facts, and therefore held certain wrong ideas, e.g. that the earth was at the center of the universe.5 But the widespread picture of how wretched society was, and the (honestly, odd and silly) notion that Medieval people preferred ignorance to knowledge—these are falsehoods unworthy of an adult intellect.

The Classical-Medieval Transition

As we touched on in our final post about Classical Antiquity, at the quasi-official fall of the West Roman Empire, almost nothing fell with it. Odovacer changed little; he even sent the imperial insignia off to Emperor Zeno in New Rome, a.k.a. Constantinople. Why should he change anything? The emperor had made him a Roman patrician and appointed him dux Italiæ (“duke of Italy”). Let’s not look a gift horse in the mouth, eh boys?

Historians debate when to say that history has stopped being Antique and properly gone Medieval on us. Some time in the sixth century tends to be favored, or occasionally the seventh. In 508, Clovis I of the Franks converted to Nicene Christianity; this would assume great importance in later centuries (especially when Charlemagne came to power). In 568, the Lombards invaded Italy, permanently removing most of the peninsula from the Byzantine orbit. In 622, the Hijrah took place, one of the defining moments in early Islam. Some historians would push the transition even later, perhaps pinning it to the Muslim invasion of Spain (711) or even the imperial coronation of Charlemagne (800)! This transitional era of the late fifth, sixth, perhaps seventh, and maybe eighth centuries is therefore classified by some as part of Late Antiquity—the period we defined in our timeline as the crisis of the third century, plus the post-crisis Empire down to 476. As we’ve discussed, the exact placement of period boundaries usually doesn’t matter. We do not propose to resolve the question here.6

In western Europe, Latin was still the tongue of education, religion, and diplomacy; Roman law, though caked over with local adjustments and grandfatherings-in, persisted in many places. But there is a real difference between the ancient and medieval worlds. What did it consist in?

“Lesser Men Without the Law”

First of all, a collection of successor states developed throughout Europe. Gone are Latin names like Aquitania, Bætica, and Gallia Narbonensis. Enter more familiar powers, like Austrasia, the Avar Khaganate, Gepidia, Lombardy, Mercia, the Vandal Kingdom, and Ystrad Clud. These places had highly varied fortunes and fates: the Vandal Kingdom was destroyed just shy of the hundred-year mark, while Austrasia is arguably still with us today (nowadays we pronounce it “France”).

[Roland] rides out, into that new-washed world of clear sun and glittering colour which we call the Middle Age (as though it were middle-aged), but which has perhaps a better right than the blown summer of the Renaissance to be called the Age of Re-birth. It is a world full of blood and grief and death and naked brutality, but also of frank emotions, innocent simplicities, and abounding self-confidence ... He is the Young Age as that age saw itself.

Dorothy L. Sayers, "Introduction" to The Song of Roland

Besides the cultural survivals of Rome, many of these new realms had innovations in common. One was a Germanic aristocracy. Various Goths had taken over the general regions of Britain, Gaul, Italy, and Spain, and were already in Germany and much of Europe further east. They were attracted by the prestige of Roman civilization, and gradually learned the vernacular Latin of the ex-imperial regions they lived in (excepting Britain, for some reason). In a way, this continued during the Viking Age7: the Normans, another branch of the Germanic family, set up domains in places as far afield as Ireland, Portugal, Russia, and even Syria.

Taken as they were with Roman culture, these nations were less keen on the Roman legal system. They preferred the one brought they with them, which let them to keep aristocratting barbarian-style in a theoretically Roman society—the “Salic law,” of which you may have heard, is a form of these codes. To generalize, these were systems in which feud and revenge were typically preferred to consensus justice, masculinity was defined in terms of violence rather than erudition, and the king might well be above the law rather than the reverse. Thus, the Gothic rulers of western Europe in the fifth to eighth centuries had two law codes: for their subjects, the Roman was retained; among themselves, they kept their own ancestral law. This may have contributed to the development of feudalism, which we shall return to.

The Least Stroke of a Pen

Speaking of culture and civilization, as little as a hundred years before 476, the most prestigious centers of learning included Carthage, Rome, and Milan, in addition to cities like Alexandria and New Rome. As the Middle Ages began, the horizon of learning shrank, and moved decidedly east. The causes for this are not fully understood. The Gothic conquests and the chaos they brought were doubtless a factor; but many of the Goths encouraged education among their subjects—there’s no running a bureaucracy without it. More mysteriously, it seems to have set in before the conquests did. Already in the late fourth century, St. Augustine, a well-educated Christian bishop, had a poor command of Greek—the very language that had originally been the distinctive mark of the civilized, and in which the New Testament itself was written! (The center was going to shift even more dramatically in a couple of centuries, but again, we will come to that.)

Nonetheless, and with qualifications, we are dealing with a culture that is—in an indirect sort of sense—extremely bookish. C. S. Lewis (whose incomparable The Discarded Image should be required reading for anyone interested in Medieval or Modern history of any kind) explains:

Medieval man was not a dreamer nor a wanderer. He was an organizer, a codifier, a builder of systems. … Though full of turbulent impulses, he was equally full of the impulse to formalize them. … There was nothing which medieval people liked better, or did better, than sorting out and tidying up. Of all our modern inventions I suspect that they would most have admired the card index.

They are bookish. They are indeed very credulous of books. They find it hard to believe that anything an old auctour8 has said is simply untrue. And they inherit a very heterogeneous collection of books; Judaic, Pagan, Platonic, Aristotelian, Stoical, Primitive Christian, Patristic. … Obviously their auctours will contradict one another. They will seem to do so even more if you ignore the distinction of kinds and take your science impartially from the poets and philosophers … If, under these conditions, one also has a great reluctance flatly to disbelieve anything in a book, then here there is obviously both an urgent need and a glorious opportunity for sorting out and tidying up. —The Discarded Image, pp. 10-11

Finally, the role of Christianity in the Roman Empire (for better or worse) now recast the Church as the new basis of civilization; and also, the basis of a new civilization. Within only a few hundred years of the beginning of the Mediævum, beyond the north, east, south, and even west of all that had ever been drawn together under the imperial eagle, there were lands that recognized and submitted to the dove of Christendom.

What value that submission had is a separate question. Answering it will form much of the meat of the next thousand years.

1Exact dates vary. In our listing of the Author Bank, we used the dates of 476 (the “fall” of the West Roman Empire) and 1517 (the beginning of the Protestant Reformation) for its beginning and end; these were conventional for much of the twentieth century.

2In the Classical period, romantic love was not quite viewed as a vice, but it was certainly seen as much more like an embarrassing illness than a possible candidate for the meaning of life.

3The Indian ancestor of chess was called chaturanga. The game spread to Persia, the Arab world, and Spain, and thence throughout Europe. The Persian way of playing proved influential: shah, “king,” is the origin of the terms “check,” “checkmate” (from shah mat, “the king is dead”), and probably “chess” itself.

4This is simply a Latin translation of “middle age”: medium ævum.

5However, please note: they did not think that it was flat. There is one known flat-earther from the Middle Ages: a sixth-century monk, Cosmas Indicopleustes. Every other educated person of his day thought he was wrong and told him so. The theory that the earth is flat was less successful in the Middle Ages than it is today.

6But the best date for the cutoff is 565, because Justinian (d. 565) was the last emperor to try to reunify the two halves of the Empire. Just sayin’.

7This can be dated, loosely, as between 793 (the sack of the abbey of Lindisfarne) and, say, around 1035 (the death of Cnut the Great, the only man to be king of Denmark, England, and Norway).

8Auctour is an old Anglo-Norman word that meant both “writer, author” and also “authority.”

Gabriel Blanchard (fl. ca. 1100-1130?) is a proud uncle of seven nephews, and has a bachelor’s degree in Classics from the University of Maryland, College Park. He has worked for CLT since 2019, where he serves as the company’s editor at large; he lives in Baltimore, MD.

If you want to hear more about the rich intellectual heritage of our civilization, be sure to check out Anchored, the official CLT podcast, hosted by our CEO and founder, Jeremy Tate. You might also like some of the essays in our “Great Conversation” series, covering topics like astronomy, citizenship, induction, language, poetry, and technology. Thank you for reading the Journal.

Published on 28th October, 2024. Page image of the abbey church of the Royal Abbey of St. Mary of Veruela (source) in northern Spain, exemplifying the spare character of Cistercian architecture.