The Great Conversation:

Authority—Part I

By Gabriel Blanchard

The question of authority impinges on practically every other field of inquiry that exists or can exist.

Though curiously omitted from Adler’s list of great ideas in the Syntopicon, authority is one of the most extensive and weighty topics in the Great Conversation. It touches on a multitude of spheres of activity—the political, the academic, the domestic, the military, the æsthetic—and has driven numberless conflicts throughout history. Indeed, there is a sense in which every conflict is a conflict of authorities, since, if both (or all) sides in a conflict consented to abide by a single authority’s verdict, and followed through on that promise, the war would be settled before it started.

And not only are conflicts in themselves wars of authority; whether they are conflicts at all, rather than mere contrasts, is very frequently a “says who” sort of question. As C. S. Lewis ruefully pointed out in the introduction to Mere Christianity, “When two Christians of different denominations start arguing, it is usually not long before one asks whether such-and-such a point ‘really matters,’ and the other replies: ‘Matter? Why, it’s absolutely essential.'”

Authority is conventionally divided into three main spheres in western thought: the family, the state, and the church. With the rise of classical Liberalism in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the notion of individual rights—as distinct not only from the state but even from the family—became more clear and definite, so that the self can be added as a fourth sphere. Moreover, starting (arguably) with the debates over Darwinism and higher criticism in the nineteenth century, the authority of academia became distinct from, and even in some circles opposed to, the authority of religion. We are thus able to speak of as many as five basic images of authority: the parent, the statesman, the priest, the scholar, and the self.

As we have already cited an apt passage from Mere Christianity, we may as well begin out of order, with religious authority. In Western Europe and the lands it has colonized, this overwhelmingly means the Catholic Church—except when it doesn’t, of course. In Germanic Europe and much of North America, it mostly means the Lutheran or Anglican traditions; in much of the United States, it means those groups and many more besides. In Eastern Europe it may mean Orthodoxy rather than Catholicism, while south of the Mediterranean it means Islam. In most cities of North America, Europe, North Africa, and western Asia, there have for centuries been enclaves where religious authority meant the leaders of the synagogue. And, not only but especially since the skepticism and rationalism of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries grew more prevalent, religious authority has for many people meant simply—nothing.

To argue from authority would be beneath the dignity of sacred doctrine, since “authority is the weakest kind of proof,” as Boethius says.

St. Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae IA.1.viii

Yet it feels difficult to dismiss all religious authority, and it is perhaps no coincidence that we see other religious traditions flourishing today despite the much-bruited “rise of the nones” (a rise which somehow always contrives to be “shocking” and “unprecedented,” despite having been a regular feature of the news for thirty years). A famous parable, originating in Indian faiths such as Buddhism, Hinduism, and Jainism, describes a group of blind men all placing their hands on different parts of an elephant—one on a leg, another on the trunk, another on a tusk, and so on—and quarreling with each other over their contradictory guesses about what it is: a tree, a snake, a spear, etc. This is meant to suggest that the differences among us are largely illusory, and borne more of our eagerness to go beyond what we actually know into “obvious” inferences we only think we know. But—is God, or reality, or whatever we shall have the elephant represent, something that all we blind men are equally good authorities about? For that matter, is the Buddhist lama who claims to have inside information about the elephant really placing himself on a level with the Jewish rabbi who maintains firmly that the God of Abraham is the only real one, and is most certainly not an elephant of any kind?

Doubtless we could all stand to restrain our egos a little, and gain nothing from embracing false dichotomies or jumping to conclusions. But insofar as defining authorities means deciding whom to trust, about what, it is quite unavoidable.

Speaking of the Catholic Church, the decision of whom to trust is highlighted with peculiar clarity in one of the central issues of the Protestant Reformation, the doctrine of sola Scriptura.* Both the Holy See and the Reformers were firmly convinced of the divine inspiration of the Bible. The question was: did God give the Church, as an institution, the power to interpret the Bible in such a way that those who denied her interpretations were wrong? not simply wrong “as far as we know,” but wrong, full-stop? Other bodies—the Eastern Orthodox, Miaphysite, and Assyrian Churches**—had answered “Yes, but we and not Catholicism constitute the Church,” while the answer given by the Protestant Reformers was “No, which is why Catholicism has ceased to be the Church” (to grossly oversimplify both situations!).

On what grounds are we to prefer one explanation over another? We might, for practical purposes, acquiesce in the decision that quelled the violence of the Thirty Years’ War: cujus regio, ejus religion, or “whose realm, his religion”; yet truth is hardly a matter of geography, and it is hard to resist Chesterton’s more scathing translation, “Render unto Cæsar the things which are God’s.” So we find that in order to settle on one authority in one realm, we will in fact have to consult with another …

Go here for Parts II (autonomy), III (the distinction of spheres), IV (the state), V (the academy), and VI (the family).

Suggested reading:

Lucretius, De Rerum Natura

Moses Maimonides, Guide for the Perplexed

Dante Alighieri, Purgatorio

John Calvin, Institutes of the Christian Religion

Blaise Pascal, Pensées

Bertrand Russell, Why I Am Not a Christian

*The other principal disputes, namely the doctrines of sola fide on the one side and transubstantiation on the other, are interesting in themselves, but here they are relevant only as examples of things most people believe or disbelieve on the basis of authority.

**There is unfortunately no simple way to clearly summarize the many-threaded history of the Church in “the East,” i.e. mainly in southeastern Europe, Western, Central, and South Asia, and the Horn of Africa. Many people are familiar with Eastern Orthodoxy, which was divided from Rome in the Great Schism of 1054. However, two other bodies split off from the main body centuries earlier; these are conventionally known as the Oriental Orthodox (whose doctrine of Christ is called miaphysitism) and the Church of the East (who today are mainly associated with the Assyrian people of norther Iraq). Since the more conventional names are quite confusing for obvious reasons, I’ve instead used Miaphysite and Assyrian.

__________________________________________________________________________________

Gabriel Blanchard is an uncle to seven nephews, and has a degree in Classics from the University of Maryland, College Park; he is CLT’s editor at large, and lives in Baltimore, MD.

If you liked this piece, check out some other installments from our great ideas series—you might enjoy our introductions to democracy, life and death (a three-part series), matter, and sameness versus otherness. Thank you for reading the Journal.

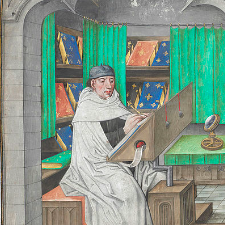

Published on 11th May, 2023. Page image of a Russian depiction of the “Quinisext Council” or “Council in Trullo,” considered invalid by Catholics, but valid by Orthodox Christians as a continuation and completion of the Second and Third Councils of Constantinople.