Rhetorica:

The Divisions of Rhetoric

By Gabriel Blanchard

"Rhetoric in its truest sense seeks to perfect men by showing them better versions of themselves, links in that chain extending up toward the ideal." —Richard Weaver1

Common Sense

As we said in this prologue’s prologue, rhetoric is the crown of the liberal arts. Grammar and logic find their culmination in rhetoric, and originally, it was these three which justly bore the title of “the humanities”: by them, and only by them, we come to understand how to use the uniquely human gift of language to the zenith of its, and our, powers. That gift underlies all other knowledge—indeed, in a real if limited sense, it is all other knowledge—and the power it bestows is twofold, that of receiving the thoughts of others and that of giving our own to them.

For this reason, it is worth mentioning that one of the functions of rhetoric is to highlight the interconnectedness of all subjects. No field exists in isolation. The study of geography illuminates political science; arithmetical analysis of music has been going on since Pythagoras; chemistry often affects our idea of history through the medium of archæology, and so on. F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote of “that most limited of all specialists, the ‘well-rounded man.'”2 It is an amusing line; but the very structure of liberal arts education implicitly maintains that it is not, in fact, a true line. The well-rounded man is not in any sense “most limited.” He is more free than most people to go on growing, in any direction.

This does not do away with the differentiation of subjects. They are connected, as all our organs (hopefully) are connected; they are not just “the same thing,” nor would this be desirable, any more than it would be desirable to let our ears go on vacation and let the pancreas do its best to fill in. Nor does this interrelation of knowledge lessen the deference due to specialists’ expertise. By learning rhetoric, I may be better prepared to understand what an astrophysicist tells me about obstacles to the existence of silicon-based life; I am no better equipped to discover them without her assistance, still less to make predictions in terms of knowledge she has and I don’t. In short, rhetoric teaches us both the unity of knowledge as a thing, independent of ourselves, and the limitations of the knowledge we actually possess.

In this way, rhetoric’s role in learning resembles a faculty our medieval ancestors called common wit or common sense.3 It is with our eyes that we see, and with our noses that we smell; common wit is the thing which tells us that what we see is vision and what we smell is scent, and which allows us to make up a composite, co-ordinated picture of our total experience.

It had grown dull as the train left the London suburbs, and even as he jumped from his compartment the first drops of rain began to fall. ... In a distance he discerned a shed by the side of the road, broke into a run, and, reaching it, took shelter with a bound which landed him in a shallow puddle lying just within the dark entrance. "Oh, damn and blast!" he cried with a great voice. "Why was this bloody world created?"

"As a sewer for the stars," a voice in front of him said. "Alternatively, to know God and to glorify him for ever."Charles Williams, War in Heaven, Ch. 8: Fardles

A Sketch of Oratory

Of course, in light of its “master key” character, the idea of offering an outline for the study of rhetoric threatens to become terribly recursive. Nonetheless, if only for practical reasons, we shall have a go at it, as we did at the beginning of our Brain User’s Manual, and again retrospectively for our series on fallacies.

The principal rhetorical sub-fields we need to discuss, then, are these:

I. Intellectual Courtesy (And Why It Matters)

A. Honesty, Courage, and Clarity (without these, all thought falls down)

B. Magnanimity—And Its Limits (it is not only kind to assume well of people, but unfair to assume otherwise, up to a point)

C. Common Ground (in practice, arguing without common ground is no better than making bald assertions)

D. Imaginative Sympathy (we are not actually being magnanimous if we refuse to take seriously the question of why others think something)

E. The Rhetorical Ear (following through on imaginative sympathy with actual listening and analysis)

F. The Wrong Fork (how conventional “good manners” do and don’t relate to intellectual courtesy—including when it’s just not time for debate)

II. The Temporal Varieties of Rhetoric

A. Forensic Rhetoric: concerned with the past (used in judicial proceedings, historical study, etc.)

B. Epideictic Rhetoric: concerned with the present (used in speeches of praise and censure, lessons, etc.)

C. Deliberative Rhetoric: concerned with the future (used in political debates, discussions of ethics, etc.)

III. The Rhetorical Appeals

A. Ēthos (appeal to character)

…1. Phronēsis (sound judgment)

…2. Aretē (virtue)

…3. Eunoia (audience rapport)

B. Pathos (appeal to emotion)

…1. Assertive vs. Fixative Emotions (i.e., those which tend to prompt swift action vs. those which tend to inhibit it)

…2. Discussion of Particular Emotions (anger, happiness, fear, etc.)

C. Logos (appeal to reasoned argument, both deductive and inductive)

IV. Rhetorical Technique

A. The Topoi (generic types of argument)

…1. Definition

…2. Analogy

…3. Relation

…4. Circumstance

…5. Authority

B. Oratory Proper

…1. Affect and Delivery (voice, face, and gesture)

…2. Register (i.e., finding language appropriate to the subject, audience, and occasion)

…3. The Structure of Formal Argument (at minimum, exordium, confirmatio, confutatio, and peroratio4)

…4. Tricks of the Trade (ways of adorning speech or writing)

1This quotation comes from Weaver’s book The Ethics of Rhetoric, from the essay “The Phædrus and the Nature of Rhetoric.”

2The line in question is from The Great Gatsby. It is worth adding that, even if the assumptions of liberal education are correct—i.e. the well-rounded man is neither useless nor incapable—it is always possible (likely, even) for a certain percentage of students thus educated to acquire little but a smattering of clever-sounding quotations from it. In times when such students are abundant, it would even be possible for an ill-informed observer to suppose, or for a well-informed one to say as a joke, that well-roundedness was a limited and limiting specialty.

3Medieval psychology identified us as having five bodily senses and five mental wits—a phrase like “he was scared out of his wits” originally referred to specifiable things. The senses were the same five we know (vision, smell, Sleepy, Bashful, etc.), while the other four wits were enumerated as memory, estimation, imagination, and fantasy. Today, we might replace the word “estimation” with “instinct,” and perhaps reclassify “imagination” as a specialized subtype of memory (it then meant the power of retaining and recalling sensory perceptions, while “fantasy” was more along the lines of imagination in the modern sense). For more on this, we recommend The Discarded Image by C. S. Lewis (1964), particularly Chapter VII: Earth and Her Inhabitants, §E. Sensitive and Vegetable Soul.

4These four Latin terms respectively mean “commencement,” “confirmation” (i.e. positive argument), “refutation,” and “conclusion.” Classical rhetoric generally expected confirmatio to be preceded by divisio, i.e., “enumeration” (of the points one is about to make); in contexts such as trials, it also expected the exordium to be followed by a narratio (“narration”), in which a prosecutor would depict the accused as guilty and an advocate would depict them as innocent, in either case arguing for consistency between their general character and their guilt or innocence.

Gabriel Blanchard was a high schooler at Rockbridge Academy (a classical school outside of Annapolis, MD) and went on to receive a degree in Classics from the University of Maryland, College Park. He is a proud uncle to seven nephews, and lives in Baltimore, MD.

If you enjoyed this piece, you might also be interested in some of the profiles we’ve written of great orators and poets on our Author Bank: these include Æschylus, Cicero, Origen, St. Bernard of Clairvaux, St. Catherine of Siena, the “Pearl” poet, Martin Luther, John Donne, Thomas Jefferson, Mary Wollstonecraft, Anna Julia Cooper, J. R. R. Tolkien, and dozens more. Thank you for reading the Journal.

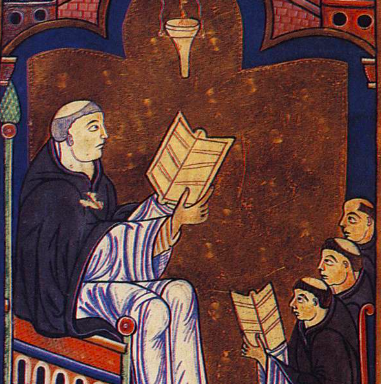

Published on 13th February, 2025. Page image of Cicero Denounces Catiline in the Roman Senate, a fresco located in the Palazzo Madama (the seat of the Senate of the Italian Republic) in Rome, painted by Cesare Maccari from 1882 to 1888. This post was updated on 27th May, 2025, to reflect small but significant alterations in the outline of the Rhetorica series following this post.