Introducing

Two New Series

Sophistries and

The Author Bank in History

By Gabriel Blanchard

What else is there to a conversation, besides who spoke in it and about what? Surprisingly: quite a bit.

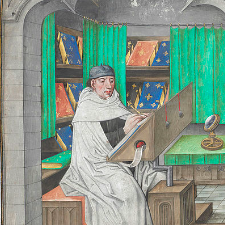

Last year, we wrapped up our regular Thursday series on “the Great Conversation,” explored topic by topic from angels to the world (indexed here). Over the next few weeks, we will be doing the same for our Monday authorship series. This has offered short profiles of the men and women who appear on our Author Bank, as well as of the handful of anonymously-written books it contains.

In the lapse of these mainstays of the Journal, the natural question becomes, what next?

On Thursdays, we will be shifting from topics of the Great Conversation to a certain set of rules about how to conduct that conversation. Any good conversation has rules, and most of them are ultimately ways of getting everybody involved to stick to the point—not unlike sports. That may sound like a strange, but think about it. In soccer, it is against the rules for players to touch the ball with their hands; in fencing, it is against the rules to attack one’s opponent before the referee gives the signal; in sprinting, it is against the rules to obtain and use rocket skates from the Acme Corporation.* In each case, why? Because the thing that makes soccer fun and interesting is the tension produced by the question, Can Team A, without using their hands, get the ball into Team B’s goal more often than B can do the same to A? That implies admirable physical and mental skills, and the satisfaction of a soccer match lies in the resolution of that tension. Spectators at a fencing match are not interested in knowing whether fencer X would be able to overpower fencer Y by taking him unawares; they know already that X probably could do that. What they don’t know, and have come to find out, is who is a better fencer. And while rocket skates, like most products of the Acme Corporation, are a capital source of entertainment, they are irrelevant to sprinting in specific, which is about the sheer speed the human body as such is capable of.

To be sure, some rules are mere conventions, and could easily be changed. But most rules (especially the big rules) exist so players and audience members can enjoy the peculiar pleasure which they go to that sport for—watching athletes subject to challenging constraints display their mastery of them.

Ninety-nine interviews out of a hundred contain more or less subtle distortions of the answers given to the questions, the questions being, moreover, in many cases, wrongly conceived for the purpose of eliciting the truth. ... Nor has the victim any redress, since to misrepresent a man's statements is no offense, unless it happens to fall within the narrow limits of the law of libel. The Press and the Law are in this condition because the public do not care whether they are being told the truth or not.

Dorothy L. Sayers, The Mind of the Maker, Preface

One of the chief pleasure-spoiling behaviors in the Great Conversation is the use of sophistries, or fallacies. The pleasure at stake is using the faculty of reason, something that, as far as we know, only humans can do. Sophistries counterfeit this. Named for the Sophists (who frequently taught pupils how to use them to manipulate legal proceedings), they present themselves as good reasoning, but are really something else: confusions of things with similar names, or appeals to emotion when emotion is not called for, or distortions of the facts under discussion. All sophistries have a common thread most clearly expressed in the red herring: they are a distraction from what we are here to do. Of his six-part work known as The Toolbox,** Aristotle devoted one part to spotting and dismantling fallacies. We will be loosely following its course, as we did with Adler and the Syntopicon: examining sophistries one by one and exposing how and why they are fallacious—or how and why, in the right context, they aren’t.

So much for Thursdays. What about Mondays?

Anyone who glances at the CLT Author Bank will immediately notice that it has been divided into four segments—Ancient, Medieval, Early Modern, and Late Modern—and that the authors in each segment are listed in the historical order of their birth. This is a particular choice, and there are other arrangements we might have used: an alphabetical listing, for instance, or (if we felt like courting the wrath of the entire world) a ranking from best to worst. But the chronological ordering points to one of the important dimensions of the Great Conversation, neatly expressed in the proverb Context is king. All speaking and writing relies on an understanding of what words mean that is shared by everybody involved, but that shared understanding changes over time. That change is why we are at risk of misunderstandings here and there, when reading the King James Bible or the plays of Shakespeare; it is even why the Romance languages are the Romance languages, plural—not simply the contemporary form of Latin. In order to get the most out of a writer (and sometimes, in order to understand them at all), we need to have some idea of the historical context in which they wrote.

We will therefore be introducing a series on the outline of history as it pertains to our Author Bank. This will be very much an outline of history: a genuinely comprehensive history, even of the Western world alone, could easily take decades to compose! But we hope to give the general reader an idea of the historical circumstances that would be the most likely to influence the Great Conversation, whether as subject matter or as mental “background.” We also want to touch on the closely-related discipline of historiography, or how and why history is written, preserved, and studied in the first place, because that strongly influences our own ideas about it (and, through those, our ideas about the present). In discussing a question like Why do we call the whole Medieval period the Dark Ages?, we are rapidly prompted to answer further, more intensely-posed questions like Wait, we don’t call it that? Then why did such-and-such an author say—what do you mean, they have no expertise in the field! Were they just … making things up this whole time? Why!?

And those can be some very interesting questions.

*That is, I assume it is against the rules. Otherwise surely everybody would be doing it.

**Or the Organon, if seeing titles translated into English just makes you sick.

__________________________________________________________________________________

Gabriel Blanchard is like this largely thanks to a degree in Classics from the University of Maryland, College Park. He is also a proud uncle to seven nephews, and lives in Baltimore, MD.

If you enjoyed this piece, you might also like our podcast, Anchored: hosted by Jeremy Tate, the CEO and founder of the Classic Learning Test, he there interviews educators, activists, and other intellectuals on questions of American education, policy, and much more. If you’d like to read more here at the Journal, take a look at this CLT student’s own account of the benefits she drew from reading the Purgatorio, our own brief analysis of just war theory, or this tutor’s comments on the often-forgotten role rhetoric and even silence can play in education.

Published on 8th January, 2024.