Texts in Context:

The Queen of the Sciences

By Gabriel Blanchard

Former crusaders returned home from the sunburnt lands of Islam, and, like Caliph al-Ma'mun, of all their spoils, the most priceless were the books.

The Prelude

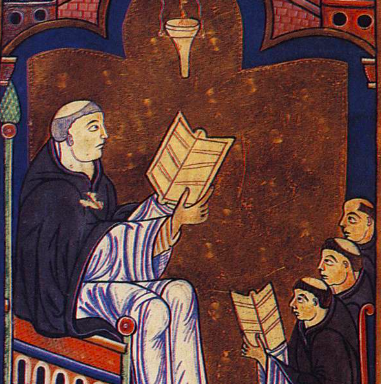

Late in the eleventh century and at the beginning of the twelfth, the curious, well-organized brains of men like St. Anselm of Canterbury and Hugh of St. Victor had begun addressing their intellects to questions of theology. Hugh was primarily a teacher; his writings improved on the tools which the cathedral schools of Charlemagne had (fitfully) spread, like the Institutiōnēs Grammaticæ of Priscian, the Ars Grammatica of Ælius Donatus (one of St. Jerome‘s teachers), Cicero‘s Dē Inventiōne and Dē Ōrātōre, and the Isagōgē of Plotinus’ student Porphyry (who had known, or at least met, Origen). A small, pleasing irony here is that the Isagōgē was essentially Porphyry’s epitome1 of the Categories. This is why even eleventh-century Scholasticism already reads as if it has learnt from Aristotle: It has learnt from Aristotle! But the ambit of that learning is, as yet, very restricted.

Anselm was more interested in seeing whether they could discover answers to theological questions by reasoning, not in opposition to divine revelation, but independently of it. He revived the old tradition of writing philosophical dialogues with one titled Cūr Deus Homō, “Why God Became Man.” He wrote his Proslogion in a more straightforwardly syllogistic form, one which partially anticipates the Method of René Descartes. Anselm there sets forth a famous—or at least, a notorious—idea known as the ontological argument for the existence of God. Anselm’s whole project could be summarized in a phrase from the Proslogion: fīdēs quærēns intellēctum, “faith seeking understanding,” and this was also the project of the Scholastic movement as a whole.

The Advent of Aristotle

This intellectual atmosphere of fresh, eager, confident energy was that to which Pope Urban II proclaimed: a war; yet a war which would, at the same time, be a pilgrimage—in fact, a holy war. At the time, this was a strange idea among Christians, especially since Muslims had hitherto been seen not as followers of a wholly separate religion, but as Christian heretics (and even heretics, who were not safe from execution by fellow Christians, were hitherto held to be immune to war from them).

Waged from 1096 to 1099, the First Crusade proved a dramatic success in the military and political senses. (What it may have been in other senses is another question, which we will not attempt to answer today). The establishment of the realms of Outremer,2 especially in conjunction with the ongoing Reconquista,2 meant that the West once again had access to the cutting edge of contemporary philosophy. And in this day and age, that meant Islamic commentaries on the works of Aristotle.

Not everyone who went on Crusade was French, obviously, but apparently the East Romans couldn’t be bothered, and referred to all the peoples of the northwest as Φράγκοι [Frangi], “Franks”; the Muslim Arabs followed suit, dubbing them الإفرنجي [al-Ifranji].3 It was certainly the case that many volumes of Muslim learning brought back to Europe from Outremer were borne by Frenchmen. It is thus fitting that the French capital became a seat of learning unparalleled in splendor: the University of Paris, which was virtually the capital of the European intellect as well. For around two hundred years, the University of Paris was one of only four in Europe that had the right to bestow degrees in theology,4 which were thus de facto the great centers of academic philosophy as well (which at this time still enfolded natural philosophy, i.e. the sciences). And when the many works of Aristotle and commentaries upon them by eminent minds of the Islamic Golden Age came to Paris, … people hated that.

The wording is important: “people,” not “everyone.” Plenty of people did admire Aristotle right from the start, like Héloïse d’Argenteuil. She is now typically spoken of, if at all, only in connection with the first bloom of the “courtly love” tradition; but this is a great pity, for she was quite possibly the single most accomplished scholar of her day. She was familiar not only with the Latin that was expected of any educated person, and the Greek that had been a rare skill in the West for centuries, but even with Hebrew, a language unknown to practically anyone in Western Europe at the time save the Jews themselves. (Small wonder that she caught the eye of another Aristotelian, Peter Abelard.)

What great advantages would philosophy give us over other men, if by studying it we could learn to govern our passions? but how humbled ought we to be when we cannot master them?

Peter Abelard, Letter III: To Héloïse5

Étienne’s Temper

But the clerical establishment was much more of the cast of Abelard’s bitter opponent, Bernard of Clairvaux. To the extent that it went in for philosophy at all, it preferred its philosophy Neoplatonic (ideally as filtered through St. Augustine), not Aristotelian. More than that, Catholic doctrine was incompatible with certain views of a philosophical school following the brilliant Muslim scholar who was known in Latin as Averroës. Based on his (and their) reading of Aristotle, the Averroists contradicted long-recognized beliefs like the immortality of the individual soul or the doctrine that God created the world (rather than it having always existed).

Criticism of and hostility to Averroism, and by extension Aristotle too, mounted into the thirteenth century, crystallizing in the person of Étienne Tempier,6 who taught at the University of Paris for some years and served as Bishop of Paris from 1268 to 1279. In 1270 he condemned thirteen propositions that he, at any rate, considered Aristotelian and/or Averroist; seven years later, he issued another condemnation which increased the number to a whopping two hundred and nineteen, including several he attributed to a recently-deceased Dominican friar—which was odd. The friar in question (Thomas by name, from the aristocracy of Norman Sicily), for all his admiration of Aristotle, had been a staunch enemy of Averroism, and not out of any general distrust of Islamic sources on the part of this friar. On the contrary, he was avowedly influenced by Avicenna‘s برهان الصديقين [burhán al-ṣiddíqín] or “proof of the truthful,” a famous argument for the necessary existence of God, which is sometimes classified alongside St. Anselm’s ontological argument. Nevertheless, Bishop Tempier apparently believed in guilt by association, and the later condemnation did real damage to Br. Thomas’s reputation for some years.

However, while Averroism faded, so did Tempier-style criticisms of it (and of its little dog, too).7 As for the friar, he was canonized a mere fifty years after his death,8 and Pope Pius V later honored St. Thomas Aquinas as a “Doctor [i.e., teacher] of the Church.” One feels that, on balance, the point in this case goes to Scholasticism.

Incidentally, that word—friar—it’s a bit of a curiosity. They’re a type of monk, right? Why is there a separate word for them? Well, thereby hangs a tale …

1In antiquity, an epitome was a summary of another work. That may sound pointless—why not get a copy of the original?—but here’s the rub. As we never need to pay it, we tend to forget the prohibitive cost (in both time and resources) involved in copying a book by hand; and remember, until the middle of the fifteenth century, there is no other kind of copy. Epitomes were therefore a pleasing compromise: they abridged things, yes, but they were easier and faster to make than full copies and much better than nothing.

2Outremer (pronounced û-trà-mêŕ) was the collective name for the Crusader states in Old French; its literal meaning is “overseas,” ultrā mare in Latin. (The states in question were the Principality of Antioch, the Kingdom of Jerusalem, the County of Edessa, and the County of Tripoli; they were mostly in modern Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine, and Syria.) The Reconquista (rĕ-kôn-kē-stà), “reconquest,” was the retaking of Iberia by Christian realms, including Aragon, Castile, Léon, Navarre, and Portugal. Both the Crusades sensu stricto and the Reconquista were justified in similar terms, as were the Albigensian and Northern Crusades.

3Those of our audience who read Greek may be slightly puzzled by Frangi, since the letters would seem to suggest Phragkoi or Phrankoi. However, the pronunciation of Byzantine Greek had by this time strayed somewhat from the spelling, more resembling Modern Greek. Also, though the present author cannot read the Arabic script, he will venture to point out that al-Ifranji is extremely pleasing to the ear.

4The other three were Cambridge, Oxford, and Rome itself. This, ah, tetrapoly was broken in 1347, when the University of Prague was added to the list; others followed later.

5This is the third in a collection often known as “the love letters of Abelard and Héloïse” (though that title gives a misleading impression of their content); it consists of six letters, composed after both had entered the cloister.

6Also referred to: 1) under the English equivalent of his first name, which is “Stephen”; or 2) as Stephanus of Orleans. For native speakers of English, his name in French can be pronounced, roughly, as ĕ-tyĕn tôm-pyā.

7This alludes of course to the fact that, in the context of a famous analogy which made the mass of people sheep under the guidance of the Catholic clergy as their shepherds, the Dominican Order (thanks to its involvement in the Inquisition, another topic we shall be obliged to return to) were known by a Latin pun as the Dominī canēs, “the Lord’s dogs.” The present author has never read, viewed, or heard of a Wizard of Oz, and doesn’t appreciate the smart look on your face, young man.

8For those less acquainted with the process of canonization, it is not uncommon for a cause to remain “stalled” at one of the earlier stages of the procedure for centuries. Martyrdom is one of the few things that can result in a more rapid canonization, so it is illustrative that St. Thomas More, who was executed in 1535, was not formally declared a saint until 1935. (Modern technological resources, which allow for easier examination of professed miracles—usually healings—have resulted in canonizations becoming faster in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, since it is easier to distinguish the unheard-of from the merely unusual.)

Gabriel Blanchard founded the Crusader state of mild pique. He works for CLT as the company’s staff writer and editor at large.

Thank you for reading the Journal and supporting the CLT. If you enjoyed this piece, and would like a little additional background on these Franks (who have essentially gone French by this point), you might appreciate our general introduction to the Middle Ages and our outline of the rise of the Carolingians; alternatively, you could try our series on the great ideas, ranging from angels and evolution to war, peace, pleasure, and pain.

Published on 24th March, 2025. Page image of Héloïse à l’Abbaye du Paraclet [“Héloïse at the Abbey of the Paraclete”] (ca. 1800-1830), by Jean-Baptiste Millet. The picture used today for the author thumbnail in fact depicts Hugh of St. Victor instructing students.