Rhetorica:

The Topoi,

II. Similarity

By Gabriel Blanchard

Analogy is one of the oldest, most prevalent devices of rhetoric; as it is written, "But without a parable spake he not unto them."

To What Shall We Liken Similarity?

The second of the topoi, or rhetorical commonplaces, is similarity (also referred to by the names analogy or resemblance); it includes its own opposite, rhetorical reasoning based on dissimilarity. This one gets a lot of mileage, partly because it is frequently viewed as the second-strongest topos, thanks to its, well, similarity to definition. To be something and to be like something are … alike.

It is also frequently used because of its variety. Similarity embraces a vast number of discursive techniques, in all sorts of fields, from drama to mathematics. Richard Weaver, a conservative rhetorician and philosopher of the mid-twentieth century, associated similarity especially with poetic and religious thought, and it is easy to see why. Readers and rhetors with a Christian background will notice that the Gospels are absolutely peppered with this topos, in the form of both parables and the argumentative structure known as the a fortiori, and often (as in the parable of the unforgiving servant) both at once. On the poetic side, not only are devices like metaphor the building blocks of poetry, there are entire forms of literature—myth, apocalypse, allegory, and roman à clef 1 are standout examples—that rely on this for their very structure, as does every form of symbolism.

The topos of similarity is incessantly to be found in writings by the men and women of our Author Bank. The Chesterton passage we glanced at when introducing the topoi is precisely an example of this device. The “metaphysical conceits” of Donne‘s poetry are a kind of reveling in similarities discovered between things that are mostly or vividly unlike each other. (Granted, his famous one about “stiff twin compasses” is opaque to most readers today, but modern lyricist Adam Young’s similar analogy is plain enough: “Circle me, and the needle moves gracefully back and forth / If my heart was a compass, you’d be north.”)

Consider the lilies of the field,2 how they grow; they toil not, neither do they spin: and yet I say unto you, that even Solomon in all his glory was not arrayed like one of these. Wherefore, if God so clothe the grass of the field, which to-day is, and to-morrow is cast into the oven, shall he not much more clothe you, O ye of little faith?

The Gospel According to St. Matthew, 6:28b-30

Yet it is important to point out that the quantitative disciplines are no less reliant on this topos: Every scientific theory assumes that the unknown will resemble the known, at least in important respects, and all human life assumes that the future will resemble the past.

A Case Study

The a fortiori, mentioned above, is worth particular attention as one of the strongest types of this topos. Ā fortiōrī is Latin for “from the stronger.” The phrase denotes arguments of the following structure, exemplified in the above quote from the Gospel of Matthew; note, however, that much of the argument is left unstated (like enthymemes3 in dialectic):

- There is some person, object, state of affairs, etc., which we may call X.

- One might not expect quality A to pertain to X, since X does have quality B.

- However, quality A does pertain to X.

- There is also some person, object, state of affairs, etc., which we’ll call Y.

- Y is similar to X in relevant ways, yet Y does not have quality B.

- So we would expect A to pertain all the more certainly (or universally, or emphatically) to Y.

Explained in terms of that structure, here is the a fortiori of “the lilies of the field,” with the inexplicit bits put in:

- There are lilies of the field (object X), which toil not, neither do they spin.

- So it seems unlikely that God would clothe them with beauty (quality A), since they are highly transient (quality B).

- However, even Solomon in all his glory (quality A) was not arrayed like one of these (object X).

- There are also ye (object Y) of little faith.

- Ye are God’s creatures, as are the lilies of the field (Relevant Similarity), but ye are not highly transient (quality B).

- Shall he not much more clothe you (quality A)?

Clearly, this is not a proof in the logical or mathematical sense; but it is clearly reasonable—and remarkably compelling. Returning to Chesterton, we find a very apt description in Part I, Chapter V of The Everlasting Man (even though he was speaking about something else in context): “We may say, if we like, that it is believed before we have time to examine it. It would be truer to say that it is accepted before there is time to believe it.”

Stop Saying “Like”

We must close on two words of caution. One is merely that some analogies aren’t very good. The fact that someone is using a topos does not mean they are using it well; real insight into similarities among things is required, and that is a form of wisdom which does not seem to be equally distributed among men (something Chesterton knew extremely well).

The other is that all analogies have limits. Two things that are exactly similar in all respects are just the same thing; at least, probably; we don’t have to get into the ontology required to answer that question rigorously, because that isn’t the point. The point is, every resemblance is incomplete and every analogy, no matter how strikingly apt, is accordingly going to break down somewhere. As Chesterton’s friend and fellow mystery author Dorothy Sayers put it, God’s fatherhood does not mean he demands first use of the bath in the morning.

1These literary forms are frequently misunderstood. To explain them very briefly: Myth is a symbolic form of storytelling (usually dealing with questions of primordial reality or universal experience) in which the symbols tend to be loosely defined and relatively unsystematic; apocalypse is a form of resistance literature (originating in Second Temple Judaism and later taken up by Christian and Gnostic authors), professing to reveal secrets of the heavenly realms and/or the future in a kind of code; allegory is a form in which most or all characters, environments, and significant objects are personified abstractions; and roman à clef (French for “novel with a key”) is essentially real gossip with the names changed. Accessible, representative examples of the four include the Theogony for myth, chapters 7-12 of the Biblical book of Daniel for apocalypse, The Pilgrim’s Progress for allegory, and Animal Farm for roman à clef. (The present writer is sincerely sorry to say your high school English teacher—though very probably a lovely person, a hard worker, and quite intelligent—was strictly incorrect in applying the word “allegory” in almost every case; the only true allegories you’re likely to have read in high school are Bunyan’s and the Inferno.)

2This is not the flower we know as the lily (which does not grow in the Galilee); it probably refers to the anemone coronaria, known by the common names “poppy anemone” or “windflower.” These are slightly smaller relatives of the buttercup, similar to it in shape and appearance, with bright red flowers.

3The word enthymeme is from the Greek ἐνθύμημα [enthümēma], meaning “in the soul” or “in the spirit,” as distinct from thoughts of the soul that receive expression in words.

Someone exactly like Gabriel Blanchard in all corporeal and spiritual characteristics is CLT’s editor at large, and lives in Baltimore, MD.

If you enjoyed this piece, and would like to read posts that are similar but not the same, we can recommend the ones on beauty, language, life and death, scripture, and technology from our “Great Conversation” series. For something dissimilar in some but not all ways, you might prefer our history series, introduced in these three posts and picking up here with pre- and proto-history and the beginning of the Bronze Age, which we’ve since carried all the way down to the end of the Western Schism in the early fifteenth century. Happy reading!

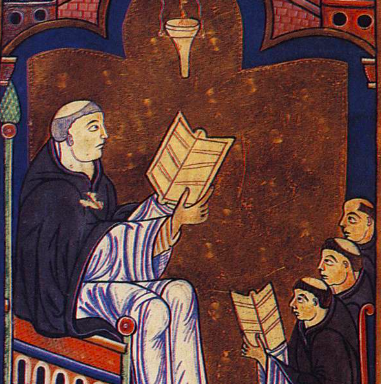

Published on 12th June, 2025. Page image of a late fourteenth or early fifteenth-century manuscript illumination by Sienese painter Martino di Bartolomeo, depicting a devil stealing a child from its crib and leaving a changeling in its place (a common trope in northern European folklore of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance).